I was reading an editorial in the New York Times that, although clearly intended as satire and meant tongue-in-cheek, struck me as fundamentally accurate. And it made me feel outmoded, given the extent to which I buy into the "code of the Higher Eclectica" as Mr Brooks put it. I feel a certain scorn, combined with a distrust, of those who base their definitions of cultural coolness on media over underlying culture. But I think it's true. It's now the iPhone generation, and cultural content has become moot – all that matters is means of transmission.

I begin to imagine a marxian-style analysis that encompasses historically and materially determined transitions in "modes of transmission" that goes above-and-beyond the classically marxist transitions in "modes of production." Let's just call it the germ of an idea, for now. Mientras tanto, digamos adios a la "Higher Eclectica" del Sr Brooks.

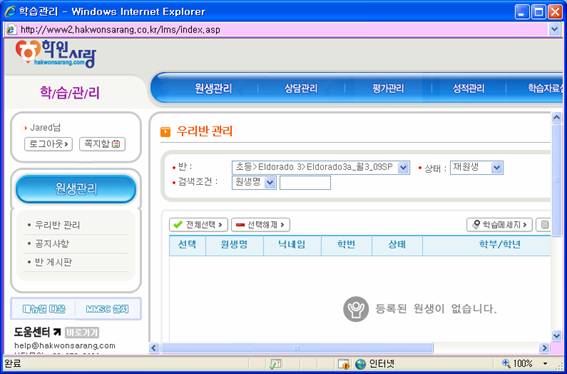

Which reminds me of a couple of lines in the latest Korean drama that I've been watching episodes of: they mention the "386" generation as being those people in their 30's and early 40's (in Korea, but it applies just as well to U.S. culture I think)–people who's formative years included personal computers but for whom the internet and broadband cellphone connectivity seem just a tad "newfangled."

Anyway, the drama is called 달자의 봄 (Dalja's Spring), and it is consistently violating all the "rules of Korean drama" that I'd decided must exist up until now. It deals with all kinds of unexpected and "taboo" subjects that every single drama I've watched up until now scrupulously avoided: divorce, suicide, abortion, premarital sex, pregnancy outside of marriage, middle-aged career women, single mothers, irresponsible fathers. And more than just blinkingly, although by U.S. standards it remains utterly G-rated.

Yet despite all that, it is a very light-hearted, even sappy romance, with a fundamentally conservative social message, just like all the Korean dramas I've watched. This message strikes me as both compelling and unrealistic vis-a-vis human day-to-day realities in any culture. And it continues to reinforce my earlier not-so-clearly-stated hypothesis that contemporary Korean culture (and perhaps East Asian culture more generally?) is undergoing a kind of Confucian counter-reformation within a modernist and/or post-modernist trajectory.

Yesterday I worked–I'd "volunteered" to help with a speech contest, and so I woke up early and went over to ElBeuRitJi's Baengma Campus, and served as a judge for lots of not-bad student speeches. It was awesome to see some of my former RingGuAPoReom students (middle schoolers) who were participating, and one of my former students, shy-but-supremely-competent Irene, even managed to win a runner-up prize, which was quite an accomplishment in the context of ElBeuRitJi's much more intense academic standards, as well as a remarkable conquest of her own reticence. I felt parentally proud, as teachers sometimes do, I suppose–Irene is one of the few students who I remember vividly from my first few days of teaching back last September, when I realized quickly that she was the quiet one feeding all the right answers to her loud and gregarious friend, Amy, who was sitting next to her.

After work, I walked home in the steaming heat of mid afternoon, all the way down past Madu-yeok and Jeongbalsan, and when I got back to my apartment I felt terrible. Tired and sickly. Perhaps I had given myself mild heat stroke or something, I don't know. But I basically passed out, feeling exhausted, and had an unpleasant night of restless sleep.

-Notes for Korean-

context: 달자의 봄

쿨하게 나가야지="act cool" (kulhage nagayaji = cool-DO-ADVERBIAL go-out-SOME-IMPERATIVE-VERB-ENDING-THAT-I-CAN'T-FIND-IN-A-BOOK)

note that 쿨 (kul) is apparently directly from English

지금 뭔가 야한 상상 하고 있었구만, 맞지?

"Now you're having some vulgar fantasy, right?"

야한=dirty, coarse, vulgar

상상=imagination

일어나다=to get up, wake up

so… 일어났어요?="you're up now?"

context: obsessing on unparseable Korean

According to the drama transcript on the KBS website, in episode 18, about 47 minutes in, grandma says:

고저 한번 잘해볼라다가 끝나는거 고거이 인생이라구 말이디.

I had tremendous difficulty trying to parse this, and I have failed. Also, as I listened to it over and over, I don't think that's what she actually says. The last words sound more like … 인생이라고 말이야, which, conveniently, I find slightly easier to parse–so I'm going to assume, with great hubris, that there's an error in the Korean written transcript, or else the transcript is meant to reflect some kind of dialectical variation and that the actress playing grandma chooses not to implement when she actually speaks. Certainly, I've never heard of a verb ending -디 before. Anyway… according to the subtitlers, the phrase is supposed to mean: "The true meaning of life is to live well once through." So, you can see why that caught my interest–a nice philosophical, aphoristic nugget. But I really have been utterly unable to parse this successfully.

With my revisions to the transcript, the transliteration would be:

goseo hanbeon jalhaebolladaga kkeutnaneungeo gogeoi insaengirago maliya

=fluctuation once well-do-try-[INTRO-WARNING?(p231 in my grammar)]-[INTERRUPTED-PAST(but can this ending attach to the previous one?)] end-GERUND-[MYSTERY-ENDING-#1] [MYSTERY-WORD-#2] life-[COPULA]-[AUX VERB -고 말다?=finish up?]

words…

고저=fluctuation

한번=once<=한=one (ADJ form)+번=time (COUNTER)

끝나다=end, come to an end

고거이=?that?

인생=human life