I haven’t really mentioned, on this here blog, the fact that over the last year I have become a consistent user of “social media” again. Unlike a decade ago, when I was quite active on facebook for a few years (and to a lesser extent, I was using the Korean social media ecosystem branded “Kakao”), this time, I’m using a social media thing called “Mastodon”. Mastodon is quite different in one important respect from the social media that most people use: it is not owned or controlled by a large, for-profit corporation. Mastodon has a similar feel to twitter (or also, facebook’s main feed, ca. 2008), but it’s “open source” and “non-profit” and “non-centralized”. That ends up being an important distinction. It has no advertising. It doesn’t manipulate what you see – you yourself completely control it – there’s no “algorithm” to struggle with.

I’m not posting this here to try to convert anyone. Everyone has their preferred social media spaces, and among my close family and friends, the readers of this here blog, that’s largely limited to that ubiquitous and amoral behemoth, facebook (which I abhor but remain engaged with in a mostly ancillary way). I have the option of “cross-posting” entries from this here blog to Mastodon, and I do so, not inevitably (I like the control) but anyway, more often than not. And on Mastodon I’ve done something I haven’t done elsewhere on social media (or the internet in general) – I’ve completely elided the long-maintained separation between my geofiction-hobby identity (aka “Luciano” aka “geofictician”) and my poem-writing-tree-photographing-Alaska-dwelling identity (aka “caveatdumptruck” aka this here blog).

If anyone is interested in exploring mastodon, they can scroll through my feed, here: https://mapstodon.space/@luciano. If you’re interested in joining (making your own account on Mastodon), go here: https://joinmastodon.org.

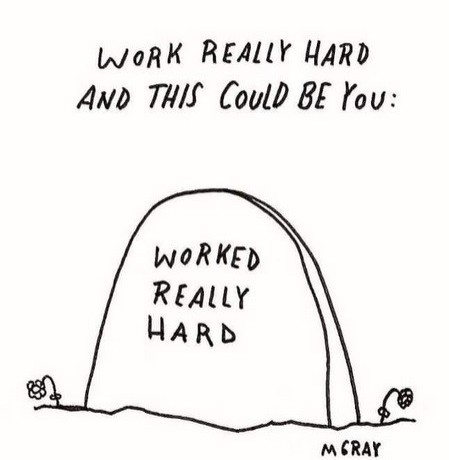

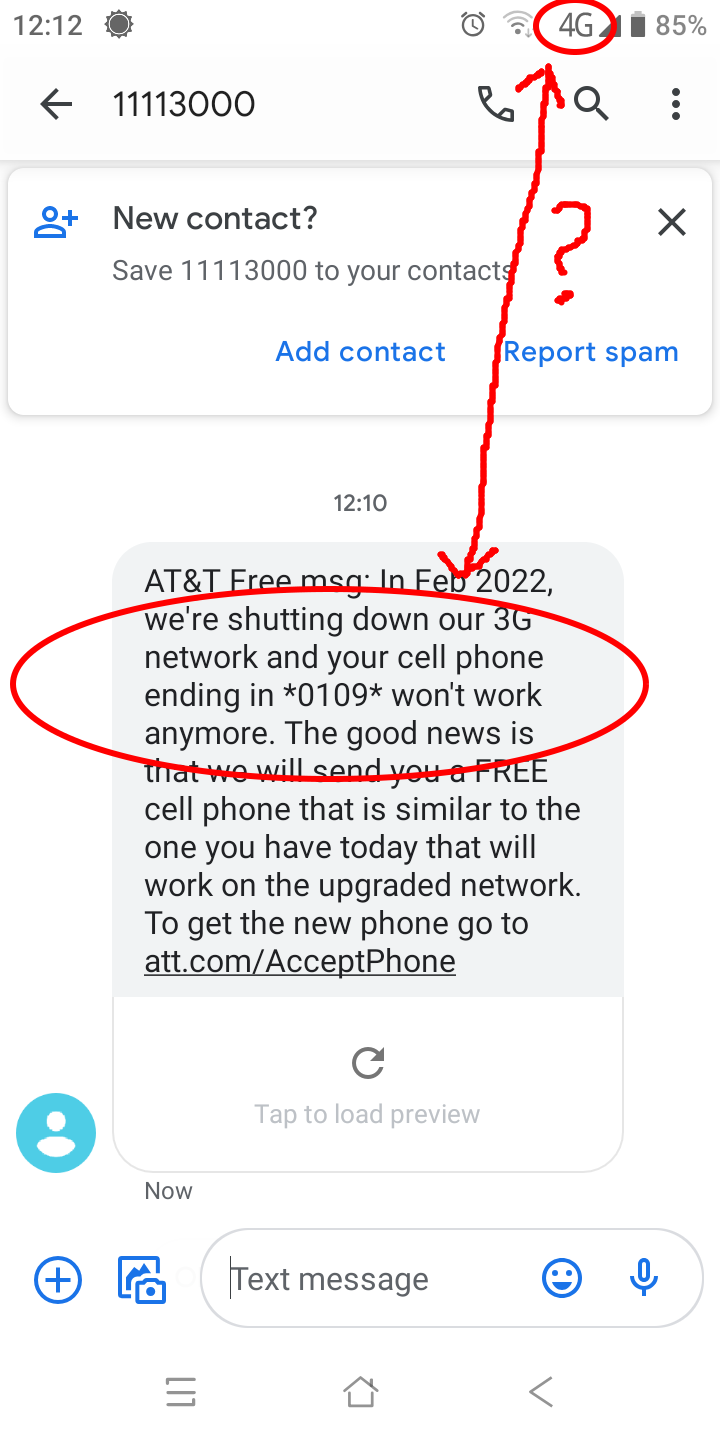

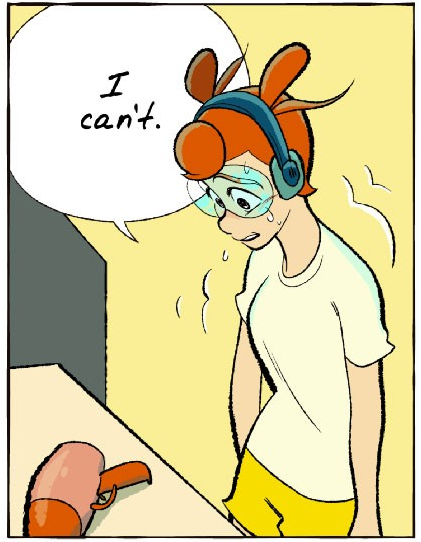

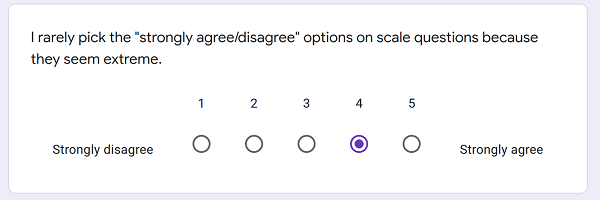

One thing that any social media is very good for is for finding amusing bits of humor and “memes” as the kids call them, these days.

I ran across this one on Mastodon, yesterday, that I rather liked.