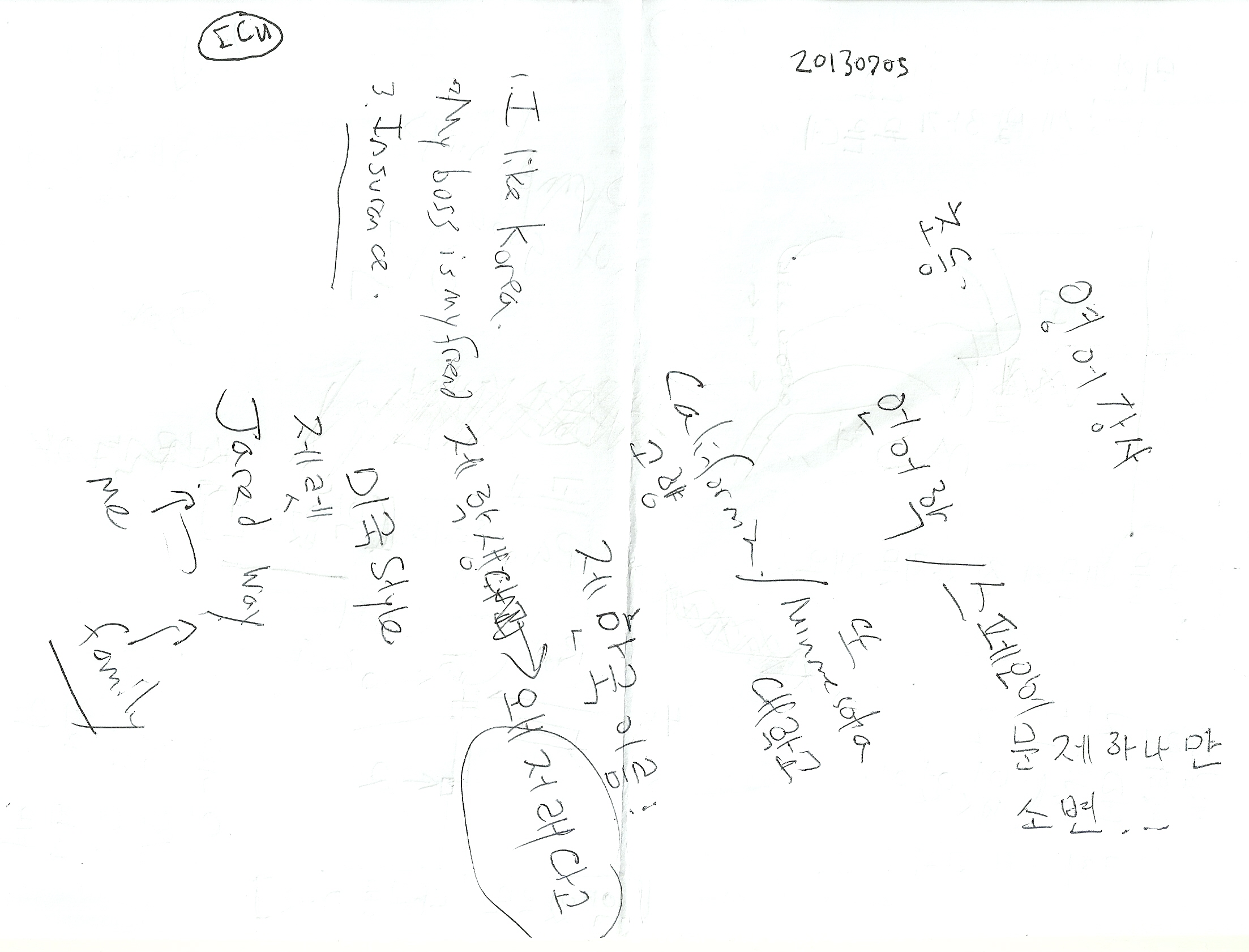

[This post and the others on this topic was written on paper in fragments or even less – single word prompts for ideas – at the time of the events – and assembled later. It’s taken a while to put things together… not through any particular emotional difficulty but just lacking the energy and willpower to do much in the weeks right after the surgery, in addition to a certain perfectionism with respect to the project which I’ve now managed to finally abandon.]

Second Shift Word: Gratitude

The following shift (my second in the ward) was a night shift: there was a

very accommodating male nurse. He was communicative, competent, friendly, and even handsome, to boot. He frequently was off assisting the other nurses, too, so it was one of my “least attended” shifts. But when he was beside me his efforts were always exactly right.

The nurses in the ICU are hardcore. But they are human, they make mistakes, too. I felt so vulnerable to them, and I felt that it was becoming a sort of human-relations puzzle to solve how to get the best care possible, given how limited my communicative abilities were.

So meditating on how to solve the problem of maximizing my quality-of-care (and really, I was thinking in those terms even in such straits), at some point between my first shift there and my second, I realized that the key is gratitude. Not just felt gratitude, as in a prayer or affirmation, but expressed gratitude.

I began trying to remember to write “고마워요” [thank you] on the corner of each new page of note paper that I was using to communicate my needs, and anytime any nurse did anything, I would point to that word – saying, in effect, thank you for doing your job. Some nurses found it amusing, or perhaps it made them uncomfortable. I’ve realized in retrospect that the ICU nurses have to work very hard to avoid emotional entanglements with their patients – especially in a cancer hospital, many of these patients are dying, and many more are in such great suffering that they are unreachable through human contact.

The sheer volume of human suffering ambient in the large ICU room was constantly palpable – there was moaning, there was crying, there was screaming, there were men yelling like babies, “아파” [it hurts!]. There were doctors rushing around reviving patients who had stopped breathing or who were lapsing into comas.

Yet this little quirk of mine, of pointing at “thank you” and making eye contact with the nurses when possible, proved remarkable. The coldness faded a little bit, and they would take extra steps to make me comfortable, or even strike up “conversations” – me writing in my pad in bad mixtures of Korean and English while they phrased simple questions about my background or situation.

I was being forced to write everthing on sheets of paper – I did not

talk at all during my time in the ICU. I wasn’t able to remember to save

some of the papers from the earlier shifts, but I believe this paper is

from the second shift – it’s me introducing myself to my nurse and

maybe some other nurse or orderly.