If only the real world had hyperlinks in it.

Today was a day off from work. I spent time hanging out with my neighbor in my building, Basil. A Palestinian-Canadian-American, he’s an interesting character. And, as of last week, a coworker – one of those “small world” things, I guess. I’d been a passing acquaintance of his since we had met each other walking around one time, and realized we were next door neighbors in our building. But now that we’re coworkers and nearby deskmates, we have more in common. So we talked for a while and hung out, and went into Seoul together, and had lunch/dinner at a middle eastern restaurant in Itaewon called Dubai. It was pretty good food, too.

But actually what I wanted to write about was the odd subway ride home. The subway was crowded, and so I stood in a corner of the subway car, and, per my usual habit, my eyes tried to find fragments of Korean to attempt to decipher. Obviously, I realize it’s impolite to read over one’s shoulder, but sometimes I can’t resist, especially when I catch something in Korean that I can actually understand.

This one woman was sending and receiving rapid-fire text messages in Korean on her cell phone (all the while reading a Japanese novel), and I read several words that I recognized, and I began to follow little isolated chunks of the conversation. One word she used that caused me to wonder, was when I read, clearly, 외국인 (foreigner), and then, a few words on, some form of 있다 (there is). Which made me wonder, intertextually, if she was perhaps texting her friend about the fact that a foreigner was reading over her shoulder. This seems unlikely, in retrospect, but it was one of those coincidences that piqued my interest, I guess. So I kept watching, circumspectly.

And then I saw the word 오블리비어스. What is that? Hm…. obeullibieoseu. Aha! Oblivious! Konglish, I thought. I don’t know what it is. I don’t think “oblivious” is a common Konglish term. So I googled it. Not right then, of course – although if I’d truly wanted to, I could have: my cellphone can surf the internet, if I pay exhorbitant rates. But the day is not far off when everyone will be able to google (or naver, or whatever comes next) anything they see, right as they see it. And then the real world will begin to grow hyperlinks.

But, meanwhile… I filed it away in my brain, and as soon as I got home, I googled it. And lo and behold, “Oblivious” is the title of a song by a Japanese musical artist named Kalafina, who appears to be popular in Korea, at least as far as I can tell. So, “oblivious” is not so much Konglish as Japanglish-borrowed-to-Korean. This made sense, given the fact she was also reading a Japanese novel at the time. She was probably reporting to her friend via text message as to what she was listening to on her MP3 player.

Anyway, I found this website/blog [UPDATE 2021-12-08: this link has rotted and I can find no replacement – sorry] dedicated to posting the lyrics of Japanese pop songs in both Japanese and Korean, and found something else intriguing that I’d never seen before – the use of hangeul (Korean writing system) to represent the Japenese language, somewhat like Konglish, of course. I wonder what this is called? Nihongeul?

Anyway, I found this website/blog [UPDATE 2021-12-08: this link has rotted and I can find no replacement – sorry] dedicated to posting the lyrics of Japanese pop songs in both Japanese and Korean, and found something else intriguing that I’d never seen before – the use of hangeul (Korean writing system) to represent the Japenese language, somewhat like Konglish, of course. I wonder what this is called? Nihongeul?

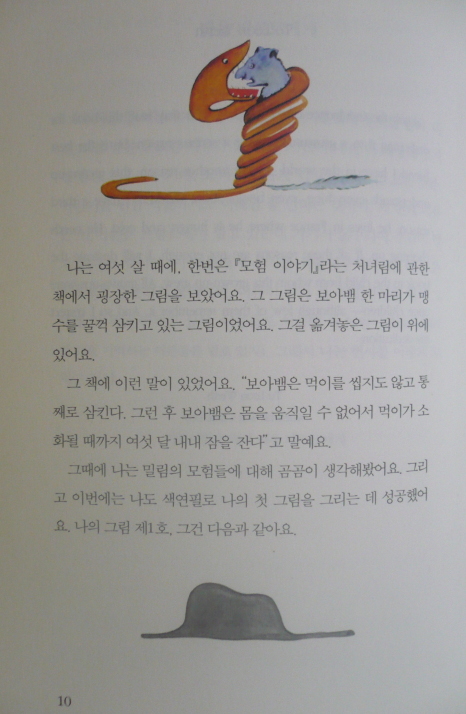

Here on the left is a sample (the website was in “Flash,” which made cut-n-paste difficult, so this is a screenshot instead). Each lyric line is given 3 times. The first line (purple) is Japanese. The second line (grey) is Japanese-in-hangeul. The third is a Korean translation. Isn’t that cool? Hmm… most of you are shaking your heads–what a language-geek!

In any event, it turns out that I really like that song by Kalafina, “Oblivious” – I’m listening to it for the third time since I discovered it. Kind of chanty and new-agey, maybe, but not bad, for JPop. And I discovered it solely because I “clicked a random hyperlink” that I happened to see while looking over a woman’s shoulder in the subway. It feels like the future, today.

[UPDATE 2021-12-08: I’ve noticed this is a very popular post for random visitors from the wider internet – probably being found via google or some other search engine. For 2021, it’s my single most visited page in this blog. So, for my visitors’ convenience, here is a link to the actual song: カラフィナ – Oblivious.]

-Notes for Korean-

너무=too much, excessively

냉채=cold mixed vegetables (basically, korean salad?)

냉-=iced, chilled, cold

쓰디쓰다=extremely bitter

뭔데?=”what is it?” (…more of that problematic -ㄴ데 ending thingy that the grammar books are so unhelpful on–perhaps it’s highly informal/idiomatic?)

오피스텔=apartment (this is actually from English, but via Japanese, I think. literally office-tel… as in office-hotel. cf. 아파트=apateu: The semantic fields work differently, 오피스텔 is the name of the individual unit in the building, 아파트 is the name of the entire building, if it’s strictly residential. To the extent the former is used at all in English, the semantic fields are exactly reversed)

사실은 나 그 애를 많이 좋아했었거든=”actually, I liked her alot” (truth-TOPIC I that kid-OBJECT much like-do-PASTPERFECT-SUPPOSITION)

context: movie titles (burning CDs to make room on my harddrive)

장화, 홍련 = rose flower, red lotus = “A Tale of two sisters”

광식이 동생 광태 = Gwangshik’s Little Brother Gwangtae=”When Romance Meets Destiny”

간큰 가족 = “A bold family”

context: words

가족=family

가장=extremely, most

![]()