The citizens of the state of Oklahoma have approved a measure (State Question 755) that prohibits the state courts from considering Sharia (islamic) law. I was sooo worried.

I continue to feel relief that I'm an expat.

The citizens of the state of Oklahoma have approved a measure (State Question 755) that prohibits the state courts from considering Sharia (islamic) law. I was sooo worried.

I continue to feel relief that I'm an expat.

Unlike 2008, I felt very little optimism about this election. I don't see myself as a typical disillusioned obamite, but I suppose the end result is the same – I failed to motivate myself to get my absentee ballot and vote in this election. The Minnesota governor's race is the only I found even vaguely compelling, but divided three ways, it seemed to me unclear what to opt for – the two options I would consider, the Independent and the Democrat, both seemed stunningly uninspiring when I heard them speaking. I like my congressman, Keith Ellison, well as could be expected, and he seemed in no danger of losing. Anyway… so I didn't vote. The whole tone of the election, nationwide, seemed just disturbing, on all sides.

I'm grateful to be an expat.

I took a "sick day," today. I'm not even really used to the idea that I actually have "sick days" – in hagwon land, there's no such thing. This is my first sick day I've taken since I started working in Korea, 3 years ago. Not the first time I've been sick, although the worst I've been sick, too, by far.

My bout with food poisoning has left me feeling pretty glum with the aftereffects on my health. I'll muddle through, but I'm not feeling my shiny, vibrant self.

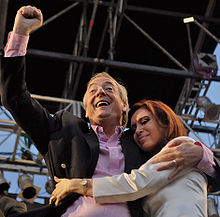

Néstor Kirchner, the last president of Argentina, and husband (“first gentleman”?) to the current president, died yesterday. He and his wife have been so frequently vilified in the US media as Argentine analogues to Venezuela’s Chávez, but in comparison to his venal and buffoonish predecessor, Carlos Menem, I think that this couple has been a profound improvement in governance (not to say perfect, obviously… corruption is relative).

Néstor Kirchner, the last president of Argentina, and husband (“first gentleman”?) to the current president, died yesterday. He and his wife have been so frequently vilified in the US media as Argentine analogues to Venezuela’s Chávez, but in comparison to his venal and buffoonish predecessor, Carlos Menem, I think that this couple has been a profound improvement in governance (not to say perfect, obviously… corruption is relative).

I’m surprised at his death – it’s clearly premature. And it rather throws a wrench into the plan of his and his wife’s to rule the newly re-branded People’s Republic of Pampas indefinitely, as an alternating diarchy. Who will replace Fernández de Kirchner, next year?

Barack Obama was on Jon Stewart's show last night. I watched it on the web. The president said, "When we promised, during the campaign, 'change you can believe in,' it wasn't 'change you can believe in' in 18 months; it was 'change you can believe in' – but you know what? – we're gonna have to work for it."

This follows on the previous night's guest, Senator Ted Kaufman (Biden's appointed replacement from Delaware), who pointed out that although the Senate is corrupt and obstructionist (not his words), it was designed to be that way. Yes, let's remember what the founders intended. So, given that as a context, perhaps former Senator Obama has an important point.

I understand the limitations of the legislative process, and recognize that the executive branch is not always (or even often) able to set legislative agendas. But I remain disappointed by him. I really thought he'd have been better able to meet the rhetorical challenges of the presidency than he's typically been, although he's had his moments.

I like Carlos Mencia. He's funny. He said:

"Want to know when you should start worrying about America? When Mexicans stop coming."

He also apparently is the origin of the suggestion that the INS start hiring the migrants they catch crossing the border to work as border guards, on conditional work permits tied to productivity – i.e. if they can't keep people out, they will get deported. This will solve the problem three ways to Sunday, and probably be cheaper than the way it's done now, given the low wages these workers could be paid. [remember, this is a joke].

About six months ago, when I was in Japan, I made the observation that Japan seemed much less “depressed” than one would expect of a country that was in the throes of a two-decades-long economic downturn. I suggested we look at it as a “sustainable recession.”

Now, The Atlantic‘s James Fallows is on board. He seems to agree with me: not that he knows what I wrote. But I know what he’s writing, and in broad terms, he seems to back up what I was observing. He says that if Japan is a failure, it may be the sort of failure we should envy.

Japan may represent a future: where a society can come to terms with – and finally end – the fetishization of never-ending economic growth.

Someone named William J Holstein (to whom I was directed by Fallows) blogs about Asia extensively. He takes on The Economist‘s editors love affair with a doom-and-gloom analysis of the Japanese economy, head on. He begins: “It is positively surreal to read what the Economist is writing about Japan while actually visiting the country. There is a major disconnect.” Definitely – I’ve noticed this too, in my loyal consumption of the magazine’s content.

His conclusion identifies an ideological engine driving the magazine’s mis-analysis. I’m not sure I completely agree, but I do think it’s worth quoting at length, because, again, it recognizes that there are alternatives to a no-holds-barred, economic-growth-at-all-costs “free market” ideology.

Why is the Economist, a normally respected publication, so wrong about Japan? I think it’s because the Economist sees itself as the bearer of the free market orthodoxy. If Japan is facing “grim” conditions amid overall “gloom,” then the Economist’s ideology is correct. No nation can be advanced and sophisticated without embracing “the market.” But if Japan is, as I argue, a country that is managing itself very well without accepting the Anglo-Saxon version of capitalism, then the Economist’s ideology is faulty. The reform of embracing market reforms does not work for everyone. It is not universal. That very simple idea is what the lads at the Economist cannot allow to take root because it undermines their intellectual legitimacy. So they persist in their doom-and-gloom analysis of Japan–even if it does not even begin to square with the reality on the ground.

A final note, pertaining to South Korea: I personally think that Korea’s economic leadership is watching Japan very closely, and always has been. And I think the Koreans may recognize that Japan, more than, say, Europe or the US, represents South Korea’s “most probable future.” I don’t think that would be a bad thing, either. The main point: Japan is not the cultural or economic basket-case that the Western media likes to portray.

Over the years, I have almost completely avoided commentary on DADT, marriage equality, and on broader gender identity issues. I have done so because I’m pretty sure that my views on these issues tend to offend (or at the least, make uncomfortable) both liberals and conservatives, activists on the left and right, equally. I’m a “deep libertarian” on these issues. Here’re a few short paragraphs, in an effort to try to summarize my beliefs and thoughts.

There is no “default” gender identity in a given human being – we each have innate tendencies, perhaps, but gender identity is something we construct as part of our socialization. I believe in nurture over nature, I suppose – with the following caveat: we don’t have much conscious control over how that nurture works out – either as children growing up ourselves, nor as parents and mentors guiding those children. I think the whole “gender identity” question would be very well-served by completely eliminating such broad-brush-strokes categories as “gay” or “straight” and recognizing that it works more like a complex, multi-dimensional rainbow spectrum of preferences, interests, likes, dislikes, fears, discomforts, etc., all under the constraints of thousands of years of evolved cultural expectations.

I hate such “typing” as is exemplified in declaring “I’m straight” or “I’m gay” – I view it as unscientific and ultimately naive. There’s little difference between that kind of “typing” and the strangely one-dimensional views of people who used to go around saying things like: “there are four races of humans: yellow, white, red, black.” Get real: it’s a continuum. The first instance of miscegenation falsifies the whole construct. Likewise, the first instance of genuinely queer gender identity (as in the person who checks “other” on the form) falsifies the gay-straight dialectic.

On the question of marriage equality, my prescription is stunningly simple, and consists of trying for a rational answer to the following question: what business does the government have in anyone’s marriage? Get the government out of the business of recognizing marriage, altogether. If two people want to derive benefits of partnership (survivorship, parenting privileges, etc.) let them form a business partnership using civil business laws that have nothing to do with cultural tradition or churches or temples or ordination, etc.

On the question of DADT, I have always been annoyed with what I perceived as a certain shallowness and misunderstanding, on the part of critics, of the human psychology behind the desperation evident in military’s insistence on DADT. Finally, someone has nailed it (see this editorial in the NYT). Dale Carpenter writes, succinctly: “Gays are to be excluded, not because of their own merits, but because we fear that some people around them might not be able to handle the truth. [DADT] is not a judgment about gays at all, but about heterosexuals.” Put another way, it’s a fear of homophobia. Homophobophobia? Metahomophobia?

Which is what I already believed. But, anecdotally, at least, Nicholas Kristof's recent editorial in NYT really hammers the fact home. I don't always find what he writes particularly compelling or even interesting, but when he editorializes on the issue of how good and universal education can transform societies, he's spot-on.

Good and universal education are way more important than "democracy," in promoting world peace. That may be a fact that makes people uncomfortable, especially Westerners accustomed to believing that the former is somehow possible only with the latter. But the facts "on the ground" seem to be irrefutable, to me.

The problem, of course, is that universal education takes a long time to produce the effect – in essence, an entire generation. Whereas "democracy" can be "imposed" (via some type of election or other) almost immediately. It suits our desire for quick results. But getting people to vote in "failed states" (e.g Afghanistan, Haiti, Somalia) solves almost nothing. Building schools and making sure they're used will, in about a generation, solve a great deal.

Hwang Jang-yeop (황장엽) recently died, I read in the news. This man was the highest ranking member of the North Korean government ever to have defected, having done so in 1997. He was notable as having been both Kim Il-sung's and later Kim Jeong-il's "ideology advisor." In the 1970's, he was chairman of the North Korean parliament.

In fact, he was basically the key author of the Juche concept, which is North Korea's official state ideology (in opposition to Marxist-Leninism, Stalinism, or Communism, which are inaccurate terms often applied to the regime in the West). Hwang Jang-yeop defected not because he'd become disillusioned with the Juche concept that he'd authored, but rather because he felt the North Korean regime was only paying lip service to it, and that the Kims (father and son) were in essence guilty of having implemented feudalism rather than any type of communism, Juche or otherwise.

He was originally embraced by the South Koreans when he came over, but during the presidencies of Kim Dae-jung and Roh Mu-hyeon, with their "sunshine policy" toward the North, he was marginalized, as those governments made efforts to avoid antagonizing Kim Jeong-il.

"no one who has ever not hired an illegal immigrant through their companies, would not in any way be responsible for the hiring of an illegal immigrant" – rightwinger Lou Dobbs, defending himself incoherently against accusations that he employed illegal immigrants. As best I can tell, through the twisted multiple negative syntax, this is a logical tautology, not unlike saying: "someone who has hired an illegal immigrant has hired an illegal immigrant." Maybe that's what he meant?

Not a perfect man. But a truly great American: liberty and justice for all – "By any means necessary."

Malcolm X. Oxford Union Debate, Dec. 3 1964 from Jason Patterson on Vimeo.

I saw this video posted on Ta-Nehisi Coates' blog. Some commenters remarked on the parallelism between X's rhetoric and the neo-constitutionalist talk of tea-party types. One commenter, however, made the difference quite clear, and stated it eloquently and simply:

There's such a thing as a right to rebellion, and the rhetoric of revolution is always at hand as a tool. But the right to rebellion requires that your rebellion be right.

New York City is justifiably famous for being one the most diverse places in the world, in human/cultural terms. But it turns out that the city is equally notable for its biodiversity, according to an article in New York magazine (that I found out about in Tom Scocca's blog). Partly, it seems that it's not just humans that land in New York City as immigrants and find the city a hosptitable place – the population of "invasive species" is huge. But it all seems to sort of work. Kind of just like the human experiment called NYC.

Interesting.

I read about things like this. I reflect on the complex coexistence of nature and urbanism that I see in a country like South Korea (which I read is the second most densely populated country in the world, after Bangladesh – if you take city-states such as Singapore and Monaco out of the running). I begin to wonder if those "population alarmists," who feel that the world is doomed due to human overpopulation, are completely wrong. Human population is, without a doubt, radically altering ecosystems – including, of course, global climate change. But… that doesn't mean that these radically altered ecosystems will necessarily "collapse" or be unsustainable.

I guess, when you get right down to it, I'm not a apocalypticist, but rather a transhumanist, in futurist matters.

"We describe ourselves as being between Iraq and a hard place." This is a brilliant pun, even as it is, but doubly so when you consider it was uttered by King Abdullah II of Jordan, in a recent interview with Jon Stewart. Jordan! … between Iraq and a hard place. Heheh.

Jon Stewart was in high form, this past week – I tend to go through a weeks' worth of episodes on a lazy weekend morning. The interview with Jimmy Carter was interesting, but mostly serves to confirm just how important Stewart has become in the broad scheme of the 21st century American polity, such as it is.

The bit that preceeded it – in which Asif Mandvi protests "Better Wages for People Protesting for Better Wages," when he discovers that some pro-union people protesting in front of Wal-Mart are in fact non-union minimum-wage-paid temp workers – was utterly fantastic and biting satire. And Larry Wilmore, as usual, is understated comic genius.

Hmm. After my fabulous trip to Suwon / Seoul / Ilsan over the holiday, my return to Yeonggwang was anti-climactic and depressing. I had a gloomy day, yesterday. I had some things I needed to get done – dull and easy-to-procrastinate things, like website maintenance and some overdue paperwork for my accountant. I did none of it. I felt annoyed with myself. I watched videos on my computer (a really funny Korean movie called 무림여대생 = My Mighty Princess, Jon Stewart and Colbert, etc.). I took a long walk. I read a chunk of several of the books I'd purchased in Seoul. I ignored the world.

I guess for each good day, there can be a not-so-good day. It's OK.

Please forgive me. Really, she did. Here it is:

" 'Refudiate,' 'misunderestimate,' 'wee-wee'd up.' English is a living language. Shakespeare liked to coin new words too. Got to celebrate it!"

—Tweet, July 18, 2010

I found this Palinism just as I was feeling annoyed with snobby "English Nazis," too. Ironic that the most popular voice of the most reactionary sector of American society should put such eloquent, less-than-140-character voice to my reaction to the grammar reactionaries.

"If dying in the desert is not a deterrent, I don't see how a threat of time in federal prison is going to be a deterrent." – someone heard speaking on NPR, (didn't catch a name) reflecting on illegal immigration.

There has been an interesting series of articles / interviews with Fidel Castro, by Jeffrey Goldberg at The Atlantic. Among other thoughts: Ahmadinejad needs to mellow out, and Cuba's communist model has failed.

My favorite part of Goldberg's interview experience – a glimpse of banal humanity behind the old dictator:

"Do you like dolphins?" Fidel asked me.

"I like dolphins a lot," I said.

I've always had a deep fascination for the "repentant dictator." Perhaps this grew out of my time in Chile, and the weirdly dysfunctional relationship that the people of that country had with their erstwhile savior and/or tormentor, Pinochet. Yesterday, I blog-mentioned Chun Doo-hwan, who was dictator of South Korea in the 1980's. What would it be like to talk to him, now, about what Korea is like, now? I would be fascinated.

I have been reading (re-reading?) parts of Michael Breen's "The Koreans." Living here, day-to-day, it's easy to forget that South Korean democracy (such as it is) is about 23 years old. That 's not very old. The dictator Chun Doo-hwan only allowed for direct presidential elections in 1987, and those elections were flawed because the state-run media (and the state pork machine) helped ensure that his hand-chosen successor, Roh Tae-woo, would be elected (although the opposition didn't help itself by splitting the opposition vote).

So in fact, although the constitutional changes 23 years ago could be said to represent the beginning of South Korean democracy, in fact, the first "normal" presidential elections weren't held until 1992. South Korean democracy is still imperfect – but I view North American democracy as rather imperfect, too. Still, those traditions, at least, have many generations of consistency and relatively smooth alternations of power. South Korea is still quite fragile, I think.

It's interesting to realize that for anyone in South Korea who is approaching middle-age, these events were formative experiences of their youth and college years. Most of us English-speaking foreigners who work and live in Korea these days are teachers. Consider the fact that all of those cryptic, middle-aged teachers and administrators you work with have vivid memories of riots, police repression, surreptitious jailings and beatings, disappearances. Your vice principal may have been throwing flaming molotov cocktails, while in university, at his principal, who was a youthful riot-police captain, ordering his men to shoot tear gas and beat the students with clubs. Or vice-versa. Perhaps some of the puzzling things we see Koreans doing could be better understood if we take these things into account.

"Our marriage is like the electoral college – it works better if you don't think about it." – Garrison Keillor in a skit about Norwegian Calvinism.

Actually, as is often the case, the caveat above is a bit misleading. I've been thinking about Afghanistan, after reading some fragments of blog posts that included a discussion of the issues entitled: "How to get out of Afghanistan." And I immediately thought about South Korea.

Now that our (by "our" I mean US) significant military presence in South Korea is in its 60th year, why does no one take seriously the idea that we need to "get out" of South Korea? Because the mission is viewed as a "success" – we have a long-standing, almost unquestionable partnership with the South Koreans.

So why is the only way to conceptualize "success" in Afghanistan couched in terms of "getting out"? I think a real, genuine geopolitical success could just as easily be conceptualized as getting to the point where conditions "on the ground" for US troops in Afghanistan are just as boring and routine as the conditions for US troops in South Korea.

I'm not saying that's the only option. But I think people who insist that "leaving Afghanistan" is the only possible way to be successful are deeply misunderstanding what the role of "enlightened military superpower" is supposed to be. Not that I agree with the idea that the US must necessarily be an enlightened military superpower – but you can't have it both ways: choosing to operate on those terms in a place like South Korea, because it's convenient and relatively painless, and then failing to operate on those same terms in a place like Afghanistan, because it's painful and inconvenient.

It seems consistency is important not just in parenting and teaching children, but in geopolitics, too.

tweegret. N. the feeling that one gets that one might be missing out, by not participating in what seems to be a largely vacuous fad called Twitter.

I felt a twinge of tweegret, this morning, for the first time, when I learned that Kim Jeong-il is tweeting. For those who are interested, he's at @uriminzok. It's apparently in Korean.

I was reading an essay by Oliver Wang, who has been guest-writing for Ta-Nehisi Coates' blog at The Atlantic magazine website (and, incidentally, Ta-Nehisi Coates is one of the highest-quality blog that I've run across, both in terms of quality of writing and depth of topics). Wang is talking about a social issues class he teaches (apparently he's a university professor of some sort). He talks about a lot of issues, but he touches on one of the ones that most interests me.

Surprisingly, illegal immigration has not been a big topic but what is surprising is that the majority of my students who write about illegal immigration as a social problem are Asian American and presumably, either immigrants themselves or the children of immigrants. Moreover, there's invariably at least one or two papers that use familiar boilerplate such as "illegal immigration is bankrupting the state" even though when I actually covered immigration, earlier in the semester, I specifically try to defuse overheated talking points such as these.

In any case, these papers by Asian American students have been a curious phenom; I've seen it happen now at least three semester in a row but I don't have a great explanation for it besides some half-hearted theory about it being some internalized model minority mentality. This is one of those, "this topic requires more research" moments.

My thoughts, regarding this: I don't think that it's Asian-Americans' role as "model minority" that creates these reactionary politics vis-a-vis immigration issues, but rather the fact of their having come from Asia in the first place – because in much of Asia (most notably in Korea and Japan, in my experience, but hardly limited to those countries, I expect), ideologies of racial purity and narratives about the overwhelming "cost" of all types of immigration (i.e. not just the financial burden but also the social costs within relatively homogeneous societies) are quite dominant.

These ideologies, I suspect, are not easily discarded by just a few generations' removal to a new and very different society / ideological setting. The contrast might be that, in comparison to East Asia, other large immigrant groups in the U.S. these days mostly hail from societies that are to one degree or another multicultural themselves, perhaps not always on the "melting pot" model of the U.S., but nevertheless… consider the mestizismo narratives of the Mexican "Raza" concept, or the castes and hierarchies (often leading to heterogeneous social subgroupings) found in many south Asian or African cultures.

South Korea is unique, and complicated.

South Korea is unique, and complicated.

Pentecostal: 30% evangelical Christian, with a strong pentecostal character to the evangelical churches.

Buddhist: 30~40% Buddhist, with at least 1000 years’ tradition of resistance to authority.

Confucian: that was the state “religion” for over 500 years, to the suppression/repression of all others.

Fascist: which of the Asian “tiger” economies isn’t at core, a remarkable – and somewhat depressing – realization of the fascist fantasy: state capitalism with majority-consensus-driven (and minority-oppressing) politics?

Republic: yes, the democracy seems to sort of work, here, although I’m personally convinced it’s a lot more fragile than many analysts seem to believe.

I don’t normally like South Park that much. But sometimes I watch it, because the social and cultural commentary can be so amazingly intelligent and deep-cutting. One such episode I caught recently was the one entitled “Margaritaville” about the way that what we believe really drives the economy. Kyle becomes a Jesus figure, and saves the economy by taking on everyone’s debt (the way that Jesus takes on everyone’s sins) and thus allowing everyone’s lives to return to normal. It’s pretty funny, but scarily accurate in the way that it explains how the government bailouts are supposed to work.

And another episode where Mickey Mouse beats the crap out of the Jonas Brothers is funny, too, although much nastier and cruder, more in alignment with the South Park norm.

[UPDATE 2024-04-18: Originally there was a link to the episodes discussed, but that link rotted and I have no replacement link. Thank you, internet!]

Two of my favorite Dubyaisms:

"I think we all agree, the past is over." — George W. Bush

And:

"I am a pitbull on the pantleg of opportunity." — George W. Bush

With a title like that, you will think I'm writing about Afghanistan, or Iraq.

But I'm not. The U.S. has had a significant, continuous military presence in South Korea since 1950 – 60 years. That makes our time in the middle east, so far, seem pretty minor. Admittedly, once the cease-fire was signed with the North in 1953, Korea didn't have the kind low-grade, sustained civil war that U.S. troops have been having to cope with in those other countries.

Perhaps if we could have installed a cozily sympathetic, hard-ass dictator like Syngman Rhee was in South Korea in Iraq or Afghanistan, we could have reached a point where the U.S. troops were out of harm's way and a very long-term occupation would have been more feasible. It's been more than clear, among the "nation builder" neocons, that Bush and company believed that they could achieve some kind of sustainable situation of this sort.

But in today's geopolitical context, installing cozy, pro-U.S. dictators ain't what it used to be. Witness how precarious Karzai's position is in Afghanistan. He'd have been getting our unequivocal support if this were still the cold war.

Actually, though, I don't mean to be writing about the these Bushian adventures. I'm thinking about South Korea, and its love-hate, push-pull affair with the U.S. I'm particularly disturbed by a recent spat that has erupted over the issue of nuclear power, nuclear fuel reprocessing, and related issues. I was reading about it in the New York Times (q.v.).

Particularly relevant and important in that article is when it quotes someone named Mr Pomper: “It is understandable why Seoul would be frustrated that India, a non-N.P.T. state, would be given this deal while South Korea, a loyal U.S. ally and N.P.T. member now in good standing, would face resistance from Washington.” [NPT means "non-proliferation treaty"]

Why, indeed? If the U.S. trusts South Korea enough to keep 30-40 thousand troops on the ground in the country, after 60 years, and under nominal unified South Korean command, at that, why not trust them to reprocess their own nuclear fuel?

I'm not even sure the end of the article is entirely relevant – whether or not Seoul wants to build nuclear weapons isn't, and shouldn't be the issue. Given the North's transgressions, it seems hard to justify – in terms of sovereignty and peninsular security – making a carte-blanche judgment against the South pursuing its own nuclear security, either via a U.S. "umbrella" (as it currently has), or via its own program (as it once briefly pursued in the 1970's).

I mean, if India and Pakistan and Israel get to keep their bombs, and Iran and North Korea can't be stopped from making theirs… that's a dangerous world. Why not South Korea, too? Let's all have bombs, together. We'll all be super-safe, right?

But… seriously: how do we stop this? How do we take control of it? Shouldn't we at least treat each other as adults capable of rational decisions? That's all that South Korea is asking that the U.S do for them, I think, with respect to the nuclear fuel issue.

Thinking about Rumsfeldian unknown unknowns. What are they? I was contriving a paradox: the epistemologist who didn't know he was one.

I'm still weirdly obsessed with the McChrystal drama. By accepting his resignation, has Obama created a MacArther-type monster, that will be a martyr and icon for the tea partiers? Isn't that dangerous? Or… has a back-room deal been cut, that will grant McChrystal some new role after an appropriate cooling-off period? I understand the chain-of-command / civilian-control argument that said "McChrystal must go," but I think this was a very risky move for Obama politically. Was there a better solution, though?

Yesterday, the staff volleyball game wasn't played – most of the teachers were all working hard preparing for some sort of inspection / observation / review that seems to be coming up. I'm not clear on the details of this. On the one hand, staff volleyball stresses me out, because I'm really very bad at volleyball, and it's mildly humiliating. On the other hand, I look forward to it because I actually understand that it is valuable in building a sense of colleague-ship and community with the Korean teachers, which is what it's "for," obviously.

As a foreign teacher, it's so easy to feel isolated and cut-off from everyone, and one thing I find myself shocked to be missing about LBridge is the "staff room" – I used to dread the staff room! But it did give me a chance to sort of gauge the "mood" of everyone, over time, whereas here, because I have my own classroom to lurk in, I'm quite isolated.

Now Obama has to worry not just about an exit strategy for Afghanistan, but he also has to worry about an exit strategy for his relationship with Gen. McChrystal – and it's looking like that "exit" has very few "success scenarios," too. He can't just fire McChrystal – since that would leave a martyred loose cannon, a la MacArther v. Truman, 1951. He can't just pat him on the head and say get back to work, since that would leave Obama looking weakened by an insubordinate military man, which is exactly the sort of grist the loony right craves.

The only way I can see Obama getting out of this relatively painlessly is to emerge from some extended head-butting with McChrystal as new best-buddies – perhaps even with a promotion for McChrystal, at least in terms of authority or responsibility, if not outright title. Which may be exactly what McChrystal was hoping for, when he loosed his tongue for the record.

Perhaps this just goes to confirm something I've long suspected about life in the world: the truly ambitious can often effectively advance their careers by means of a well-placed insubordination. McChrystal is someone accustomed to taking risks. This may all have been a very calculated, manipulative, and inconveniently but necessarily very public request for a heart-to-heart meeting with the boss, and not the gaffe everyone insists on calling it.

How long until they come knocking on my door. I was online last night, and I was following a trail of articles about North Korea’s soccer team, which is playing in the World Cup in South Africa this year, in the championship for the first time since 1966. We had been talking briefly about it in my 6th grade after-school class yesterday afternoon.

This got me onto the subject of 정대세 (Jeong Dae-se), the North’s star player (see picture). He is, in fact, Korean-Japanese, and has never lived in North Korea (except for recent stints training with the national team). He plays for a pro team in Japan, has done television ads and product sponsorships for South Korean media, and is very publicity-savvy. A fascinating member of the “Chongryon,” which is a weird semi-for-profit pro-North-Korean organization in Japan, that runs everything from businesses to schools to functioning as the North’s de facto embassy to the Western world (since the North has few formalized diplomatic relations). I guess this soccer player grew up attending Chongryon schools.

This got me onto the subject of 정대세 (Jeong Dae-se), the North’s star player (see picture). He is, in fact, Korean-Japanese, and has never lived in North Korea (except for recent stints training with the national team). He plays for a pro team in Japan, has done television ads and product sponsorships for South Korean media, and is very publicity-savvy. A fascinating member of the “Chongryon,” which is a weird semi-for-profit pro-North-Korean organization in Japan, that runs everything from businesses to schools to functioning as the North’s de facto embassy to the Western world (since the North has few formalized diplomatic relations). I guess this soccer player grew up attending Chongryon schools.

So I was looking at Chongryon in wikipedialand, and getting all fascinated. And so, curiously, I decided to follow a link to Korea University, which is the Chongryon-run university in Tokyo (hence a training-ground in the North’s official ideology of Juche, among other things. Juche has always fascinated me.

And there, instead of viewing the Korea University website, I was looking at a very scary “police warning” page (in Korean, of course), saying the site was deemed dangerous and banned. Hmm….

One doesn’t run up against the Korean national police firewall very often (at least in my experience). I wonder if they’re going to come looking for me, or open a file in Seoul? Will they come knocking on my door?

I was listening to Harry Shearer, who always has some scathingly sarcastic things to say about current events. And he said…

In Canada, apparently, there is a regulation (a simple regulation such as could be implemented in the U.S. without even the approval of Congress, since it's at the level of the sort of thing the EPA could do by decree) that says that when an oil well is dug, a "relief well" must be added within the same season. If such a regulation had been in place – and obeyed, obviously – in the Gulf of Mexico, then BP's "missing solution" to the oil leak problem would have already been in place, and the oil would not currently be flowing into the Gulf.

Thanks Harry.

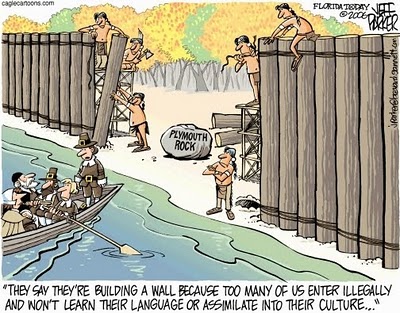

This cartoon summarizes, perfectly, my feelings about the immigration debate.

This cartoon summarizes, perfectly, my feelings about the immigration debate.

When those who oppose immigration, legal or illegal, have each taken the time and made the effort to learn at least one Native American language, and have considered the merits of Native American spirituality and culture and “walked a mile in their shoes,” only then will I take their arguments about the need to “control” immigration, and their sanctimonious arguments about “rule of law,” at all seriously.

Until then, I think Herman Melville (160 years ago!) summed up the only, truly ethical stance on immigration quite succinctly, when he wrote: “If they can get here, they have God’s right to come.”

Period.

So now that I have some internets, I’ve been doing some surfing around.

So now that I have some internets, I’ve been doing some surfing around.

There’s a guy who goes by the nom-de-twit of Leroy Stick, who is apparently behind the fake BP PR tweets on twitter that have been such a hit. A sampling:

Not only are we dropping a top hat on the oil spill, we’re going to throw in a cane and monocle as well. Keeping it classy.

I found his press release on Huffington Post, and he actually seems pretty smart. I really like the following line:

You know the best way to get the public to respect your brand? Have a respectable brand. Offer a great, innovative product and make responsible, ethical business decisions.

This is brand management 101 – and it’s why 90% of marketing people don’t get it. And why the remaining 10% of marketing people are the secret masters-of-the-universe behind the magic of ethical capitalism, by functioning as the watchdogs that keep businesses honest. And it’s why I don’t believe that marketing as a profession is a bad thing. It can be – and often is – a bad thing. But it can also be right up there with saving the world. Too bad BP doesn’t seem to have any of those types of marketing geniuses on staff.

Yesterday was election day, in Korea. Which is a sort of public holiday. Most countries either hold elections on a day when people are off anyway (like Sunday), or else they don't give people a holiday, but accommodate the need of workers to take some time off from work to vote. But Korea makes everybody take the day off – except small businesspeople, I suppose – there were still some guys banging on metal stuff in the factory-like establishment across the road from my new apartment.

Anyway, I kind of avoided going out in public. The whole election thing is a bit overwhelming, with trucks and dancing girls and bowing campaign workers beside major highways and loudspeakers and crazy campaign jingles. I just hid in my room, feeling kind of moody.

I'm convinced more and more that the 하나라 party is basically a front for the reactionary Christian right, in Korea, much the way that the Republicans have gotten more and more that way in the US, abandoning their secular conservative and libertarian roots. For that reason, although I don't agree with everything the 민주 stand for, I was hoping they'd do well in the elections, mostly to register a protest against 이명박's administration, since these are local-only, mid-term elections.

I watched the election results on the TV this morning, and it was a mixed bag: 하나라 won the Seoul and Gyeonggi governorships, looks like, which are the two largest and influential constituencies that voted. But overall 민주당 seems to have done better than I was expecting. I was surprised by the number of independents who did well, too, especially in counties and towns in the southern part of the country.

I have seen so little discussion of Obama's character that I find genuinely plausible, at a core level.

Ta-Nehisi Coates, blogging for The Atlantic, recently, finally managed to strike a chord for me. He writes:

"My sense, in reading about Obama before he was a national politician or even a politician at all, is that this kind of cultural conservatism is genuine and not a ploy. There's a section in The Bridge where, having graduated from Columbia, Obama becomes a kind of ascetic and basically tries to remove himself from all the worldly things that tend to tempt men. It reminded very much of the kind of thing you see black men go through in prison, the most obvious being Malcolm X. Indeed, I've always thought there was something of Malcolm in Obama–the mix of humor and sternness, the notion of re-invention, the cultural conservatism."

The implication is that far from being the kind of left-wing liberal that the Right caricatures him to be, Obama is a kind of "radical centrist," which, in the long run, they should be much more worried about – because he's the embodiment of what happens when "by any means necessary" meets head-to-head, and then merges, with pragmatism, ambition and perhaps, even, compassion. Indeed, maybe Obama's a sort of "compassionate conservative."