I don't like sudoku. Nor do I like crosswords, chess, "brain-teaser" puzzles, etc. I feel like this fact about myself is somehow a serious violation (nay, betrayal) of my nerdly origins, that I'm like this. But, I've always lacked enthusiasm for these types of mental recreations. One memorable example: I remember when Rubic's Cube first came out, and everyone was obsessively trying to solve it. I managed to solve it – it wasn't easy, but I managed – but I genuinely recall my efforts to do so as a profoundly unpleasant experience. I never picked it up again. Even today, when I see a Rubik's Cube, I have a sort of visceral reaction of strong distaste, similar to how I react to seeing bananas (to which – it has been verified – I am allergic).

My theory is that this gut reaction is because my perfectionism is stronger, and receives higher priority, than my intellectual curiosity. That doesn't sound like a very good reflection on my personality. And… it's not. But I'm trying to be honest about things, here.

Anyway, that's not what I meant to write about. I had a major insight, yesterday.

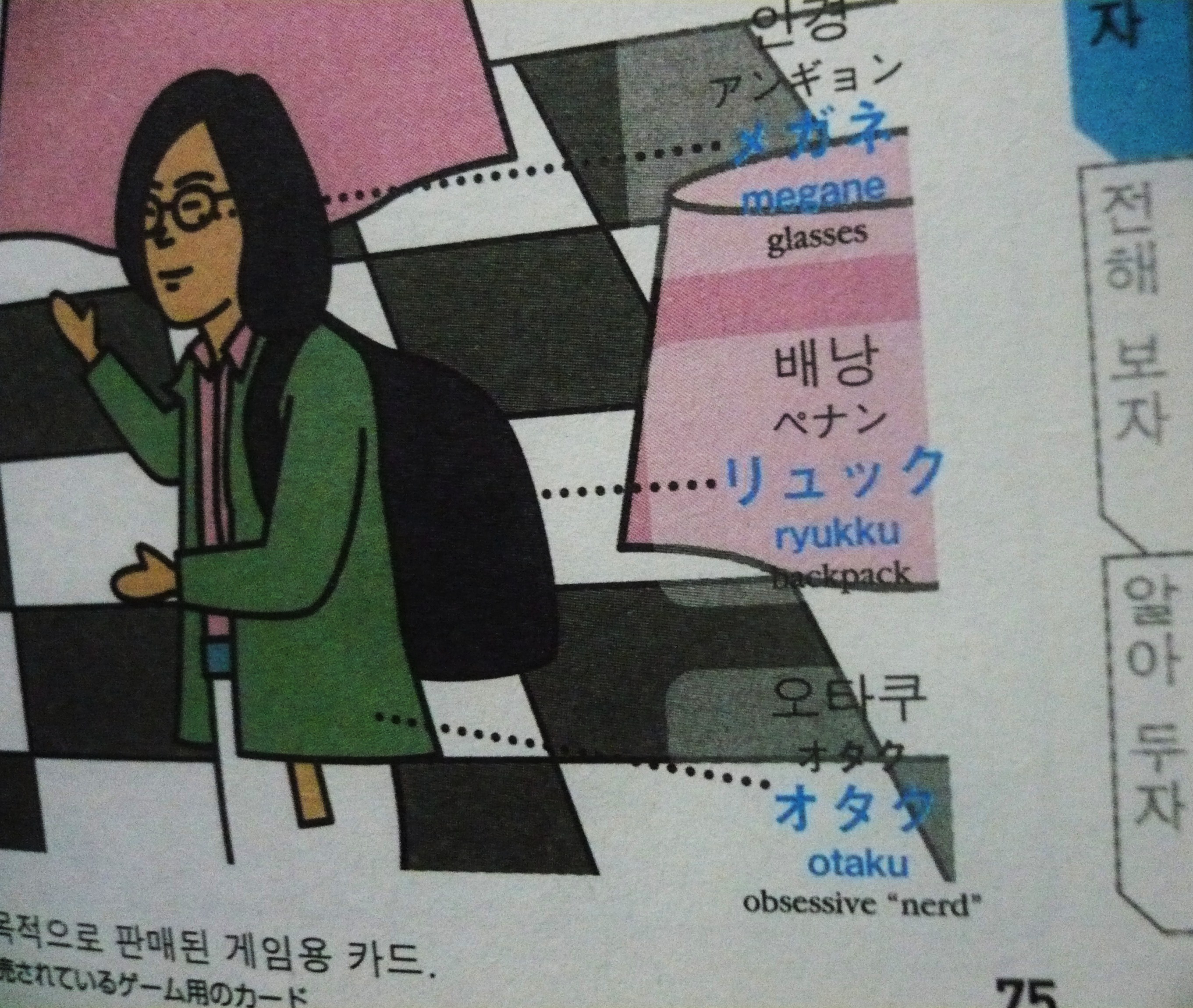

I'd decided to dedicate some more time to working through the Rosetta Stone software I'd splurged on last fall. I've been pretty unhappy with it, and so it's hard for me to motivate to use it. I have only managed to work up to around the middle of the Level 1 Korean package.

So I was slogging through it… I see the value in it, in building some automaticity with respect to grammar points and vocabulary. My core criticisms remain the same: it's not very linguistically sophisticated in its presentation of material (especially of phonological issues and grammar); the speaking sections' "listener/analyzer/scorer" is majorly wonky (I sometimes get so frustrated I just start cussing at it, which tends to lower my score); the grammar points covered sometimes don't match the way actual Koreans around me actually speak, in my experience.

But I found a new reason why I don't like Rosetta Stone, and I found it in a surprising way. I was reading a recent issue of the Atlantic magazine, and there was an ad for Rosetta Stone. And the ad said something to the gist of: "if you like sudoku, you'll love learning a language with Rosetta Stone."

You can see where this is going, right? Rosetta's software is deliberately designed to activate the same mental processes and reward centers that puzzle-games like sudoku do. And therefore it's suddenly obvious why I spend most of my time when trying to use the software feeling frustrated and pissed-off. It's the same reason I feel constantly frustrated and pissed-off when I try to solve sudoku puzzles, or play chess, or other things like that. I just don't enjoy that type of intellectual challenge.

But this insight also forces me to temper my criticism of Rosetta Stone substantially, in one respect: it means that it's just my idiosyncrasy, in part, that causes me not to like it, and to regret having bought it. If you're like most reasonably intellectual people, and enjoy killing some time solving sudoku or playing chess or the like, then, probably, Rosetta Stone is a great tool for learning a language. You'll probably think it's really fun.

Sigh.

So… there.