This woman rocks Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Chile” on a traditional Korean instrument called a 가야금 [gayageum].

Note: the term “Chile” in the name of the song should be pronounced roughly /chail/ (hence my transcription to hangeul above) – it is not a derivation of the name of the country “Chile” nor is it related to “chili” peppers. It’s rather meant to be an approximated spelling of the dialect pronounciation of the word “child” without the “-d” sound at the end.

Category: Language & Linguistics

Caveat: 말이야 좋지

말이야 좋지

word-CONTR good-SUSP

Words are good [but…]

I understand this almost perfectly but I’m just as almost clueless how to understand the grammar of it.

It’s not really a complete sentence – the “-지” ending on the verb stem “좋” is what I think of as a contingent negative, a sort of non-finite subjunctive or something like that (in saying that, I don’t mean to offer some alternative interpretation to the formal linguistic description – e.g. Martin calls it a “suspective” ending, but that term [like most of Martin’s] seems rather misleading [or limiting] about usage). So you could read the verb as “I suppose it’s good” and then you add the contrastive “-이야” on the noun “말” which means all kinds of things, but mostly “words.”

So eventually you get something like “Sure, words are good, but…”

In fact, this phrase basically seems to mean: “The road to hell is paved with good intentions.”

Caveat: Cha

I said to my student, "Whatcha doin?"

He shrugged.

"Do you understand my question?" I asked. He was a fairly advanced student.

He shook his head.

I slowed it down, but I deliberately retained the phonological contractions, because I had an intuition as to the problem, and I was curious. "What cha doin?" I repeated. I was turning it into a lesson.

There was a long pause. Then he asked, "What is 'cha'?" He was perplexed.

Indeed. Here's the thing: he's not a beginning student. If ever there was a sign that the kids need more interaction with native speakers, this was it.

Caveat: A Saliency-Based Case-Marking System?

I had another typical hermetic Sunday, yesterday. I successfully shut off my computer and phone and tried to exist on my own. It was hard. It was starting to rain, and I didn't take a long walk.

I read some parts of Paradise Lost. I don't really like it, but it's one of those gaps in my literary background that I feel needs filling in. So then I was trying to study Korean. That frustrated me, too.

My mother and I traded some emails recently on the topic of pronoun mis-use. Apparently in my blog in a recent entry, I'd written "a picture of my friend and I" when, grammatically, it should have been "a picture of my friend and me." This is use of "I" in the object case is called "hypercorrection" because it has in the past been perceived by linguists as some kind of response to too much correction by teachers of students' mis-use of "me" in the subject case: it is long-established that colloquial English allows "Me and him went to the store," while grammar teachers abhor it.

Here's what I wrote in my email to my mom.

I had one idea (thought? observation?) about it. Some languages mark

something like noun case on the basis of things other than grammatical

role. As a relevant example, Korean includes grammatical role in its

case marking particles, but these particles also include things like

conjunctive and topical markers that are added to words on the basis of

things like psychological saliency-to-the-speaker. I have been

speculating that a lot of the "drift" we see in colloquial English

around the "mis-use" of pronoun case (e.g. "Me and him went to the party,

but that's a secret just between you and I") is that English's case

system, being so weak and "unmarked" in most situations (i.e. nouns

don't show it anymore, and some pronouns don't either – e.g. "you") that

the grammatical underpinning of the system has begun to float around,

and other aspects that can influence a case-marking system, such as

saliency (in e.g. Korean or Japanese), are coming into play.

If

in just a short 1000 years English can evolve a grammatical system more

similar Chinese than its indo-european brethren, why couldn't it just as

easily begin to evolve a case-marking system similar to Korean (I'm not talking about the particles/agglutinative aspect, but just that there might be something evolving like a "topic" case where the grammatical role plays no part in its deployment)?

What I'm listening to right now.

King Crimson, "Elephant Talk." But what case are their pronouns in?

Caveat: E dels cinc non m’entendon tréi

Desirat ai, enquer desir

E voil ades mais desirar

Que tener ma dona e baisar

E luec on m'en pogues jausir !

Qu'eu l'am e dic ço que dir déi.

E dels cinc non m'entendon tréi,

Anz diran "Ben vos es esprés".

Si mon joi non avia,

Als bons fa piez.

– Pèire Cardenal (poem written maybe 1201 AD).

Cardenal was poet and troubador of the middle ages from what is in modern times the south of France, but at that time was called Pays d'Oc (the land of people who say "yes" by using the word "oc", roughly). In contemporary times, their language is called Occitan and is still spoken by several millions. It's closely related to Catalan.

I couldn't find a translation this couplet in English online. I found this French translation at a site with much of Cardenal's work.

J'ai désiré ma dame, je la désire encore

et je veux la désirer toujours et davantage

plutôt que d'obtenir de la serrer, de l'embrasser,

en un lieu où d'elle je tirerais grand plaisir.

Car je l'aime et je dis ce que je dois dire.

Trois sur cinq ne me comprennent pas

mais diront " Vous êtes bien épris !"

Et si d'elle je n'avais pas une vraie joie d'amour,

c'est qu'aux meilleurs elle réserve ses rigueurs…

So I attempted my own translation – it's a tossup whether I find the Occitan original or the French translation easier – my work with medival Spanish actually makes the Occitan pretty easy to sort out.

Couplet V

I wanted my lady, I wanted her more

And I want to want even more

Holding my lady and kissing her

Where I would give her pleasure!

Because I love her and I say what I have to say.

Three out of five do not understand me

But say "You are just infatuated"

If I did not have joy,

At best she'd take it easy on me…

If anyone harbored any doubts, this blog post should be clear evidence of my genuine eccentricity: on some days, this is my hobby.

What I'm listening to right now.

Claude Marti, "Pèire Cardenal – Razos es qu'ieu m'esbaudei." The poetry is 13th century (another work by Cardenal), but I suspect the musical setting is modern.

Lyrics.

Razos es qu'ieu m'esbaudei

E sia jauzens e gais

E diga cansos e lais

E un sirventes desplei,

Quar leialtatz a vencut

Falsetat, e non a gaire

Quez ieu ai auzit retraire

Qu'us fortz trachers a perdut

Son poder e sa vertut.Dieus fa, e fara e fei,

Aissi com es Dieus verais,

Drech als pros e als savais

E merce, segon lur lei.

Quar a la paia van tut,

L'enganat e l'enganaire,

Si com Abels a son fraire.

Que-l trachor seran destrut

E li trait ben vengut.Dieu prec que trachors barrei

E los degol e los abais

Aissi con fes los Algais,

Quar son de peior trafei.

Quez aisso es ben sauput:

Pieger es trachers que laire,

Qu'atressi com hom pot faire

De convers monge tondut,

Fai hom de trachor pendut.De lops e de fedas vei

Que de las fedas son mais,

E per un austor que nais

Son mil perditz, fe qu'ie'us dei.

Az aisso es conogut

Que hom murtriers ni raubaire

Non plas tant a Dieu lo paire

Ni tant non ama son frut

Com fai del pobol menut.Assatz pot aver arnei

E cavals ferrans e bais

E tors e murs e palais

Rics hom, sol que Dieu renei.

Doncs ben a lo sen perdut

Aquel acui es veiaire

Que tollen l'autrui repaire

Deia venir a salut,

Ni-l dons Dieus quar a tolgut.Quar Dieus ten son arc tendut,

E trai aqui on deu traire

E fai lo colp que deu faire:

A quecs si com a mergut,

Segon vizi o vertut.

Caveat: Frisco

An American named Satoshi Kanazawa blogs at the site Big Think about the need for a word that means an anti-shibboleth – meaning, I guess, more concisely than the term "anti-shibboleth" conveys. Rather than trying to explain, go ahead and read his article. To understand, you need to know what shibboleth means, too.

He proposes the word "frisco" as the new term for "anti-shibboleth." As a born and raised Northern Californian, I understand his suggestion completely, and I like the repurposing of the word. So, whenever you need to say "anti-shibboleth" – and, c'mon, I know you say it often! – say "frisco" instead. I hope his terminological innovation catches on.

Caveat: Na’iya tehmil-me’q hay-yo:w la:yxw ‘e:na:ng’?

It’s amazing, the things that can now be found online.

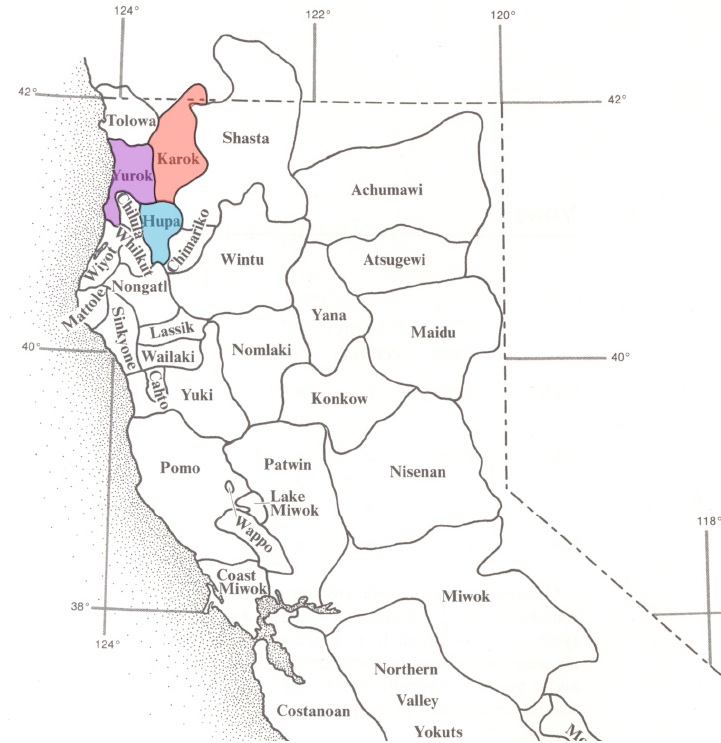

I have for a long time had a strong interest in Native American languages. In college, I studied Dakota (the Sioux language of Minnesota and Manitoba, and a close sibling of Lakota, the Sioux language of North and South Dakota), and later I studied Mapudungun (the language of the Mapuche people of western Patagonia, in south-central Chile and parts of western Argentina). I only remember a few phrases from each language, but I have occasionally even thought that, if I ever returned to graduate school, it would be in linguistics and that I would actively pursue various Native languages further.

I have for a long time had a strong interest in Native American languages. In college, I studied Dakota (the Sioux language of Minnesota and Manitoba, and a close sibling of Lakota, the Sioux language of North and South Dakota), and later I studied Mapudungun (the language of the Mapuche people of western Patagonia, in south-central Chile and parts of western Argentina). I only remember a few phrases from each language, but I have occasionally even thought that, if I ever returned to graduate school, it would be in linguistics and that I would actively pursue various Native languages further.

Anyway, I was reading an online article at the GeoCurrents blog about the revitalization of some of the languages of northwestern California, including Hupa, Yurok and Karuk. I never studied those languages, but having grown up in those linguistic lands (California’s Humboldt County, behind the redwood curtain), I have always had a strong curiosity about them. Some years ago, I had once even picked up a grammar, lexicon and story collection for Wiyot, another Humboldtian Native language that is, sadly, now extinct (i.e. it has no speakers remaining).

Apparently, there is a younger generation of enthusiasts for revitalizing the three fading languages, each of which have dwindled to less than 20 native speakers each. So the languages are being taught and studied in schools.

And then, I found this story, below, in the comments section for this article, in a comment by someone named Tim Upham. Cursory online research only explains that it’s an “original composition” in Hupa – it’s not clear whether by him or someone he knows or read about, but the same name “Tim Upham” has cited the story in other comments on other websites, online – it’s the only online “presence” for the story.

But I like the story, and I like the fact that the original language is included – as a linguistics geek, that’s half the fun. I can’t really vouch for the Hupa as “real” Hupa – I played around with an online Hupa dictionary for a little bit, trying to figure out which of the words in the last line was “rain,” but I failed. My best guess is that the first word of the last line “na’iya” bears a plausible inflectional or derivational relationship with the lexical entry “na:nyay” = rain. If anyone has any insights or thoughts on this, I’d be happy to hear from you.

A story in Hupa goes:

Xantehitaw ch’iqal.

Da:ywho’ xontah ne:s sa’an.

Kehitsan xosing xa’k’iwhe inyektaw.

Xontak ch’ing xa:singya:wh.

Nahxa kilexich ya’ng’e’ti’.

Diydi hayde’ hay tehmil?

Na’iya tehmil-me’q hay-yo:w la:yxw ‘e:na:ng’?Coyote is walking.

There was a long house standing somewhere.

A bunch of girls are digging Indian potatoes. (They are an edible tuber, sometimes known as groundnuts.)

Come on up to the house.

Two boys were sitting there.

What is in that sack?

It is only Rain there in the sack.

Caveat: inquieto vaga-lume

Círculo Vicioso

Bailando no ar, gemia inquieto vaga-lume:

– Quem me dera que fosse aquela loura estrela,

que arde no eterno azul, como uma eterna vela !

Mas a estrela, fitando a lua, com ciúme:– Pudesse eu copiar o transparente lume,

que, da grega coluna á gótica janela,

contemplou, suspirosa, a fronte amada e bela !

Mas a lua, fitando o sol, com azedume:– Misera ! tivesse eu aquela enorme, aquela

claridade imortal, que toda a luz resume !

Mas o sol, inclinando a rutila capela:– Pesa-me esta brilhante aureola de nume…

Enfara-me esta azul e desmedida umbela…

Porque não nasci eu um simples vaga-lume?

– Machado de Assis

Estou pensando também em círculos.

Eu estou ouvindo agora mesmo.

Antonio Carlos Jobim, "Batidinha."

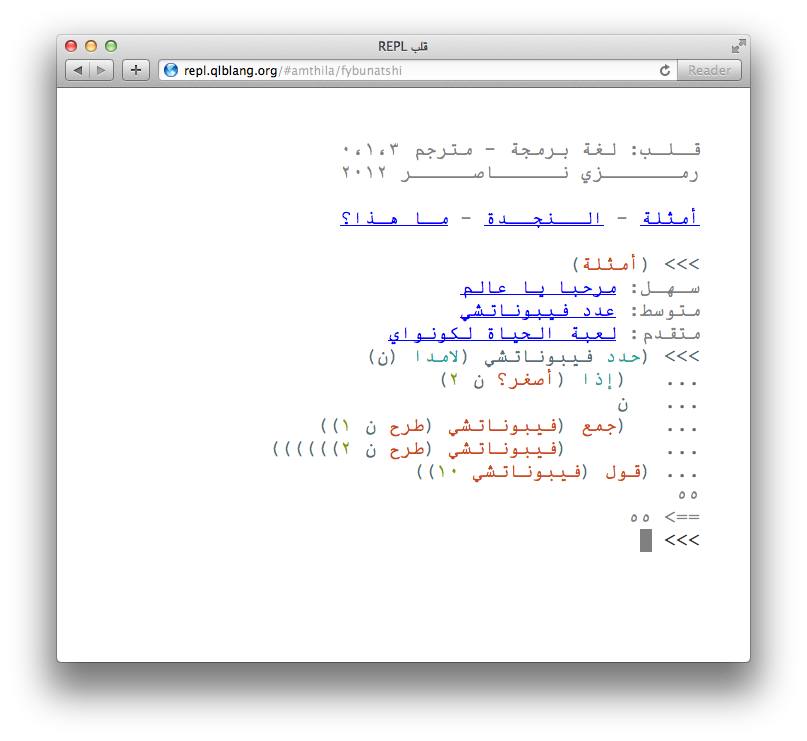

Caveat: قلب

The thing about computer programming languages is that they’re all weird subsets of English, basically (BASICally?).

This was always both interesting and disturbing to me, as a linguist. I have been fascinated by the idea of possible alternatives to that Engish hegemony. Finally, someone is doing something about it – not that it will go anywhere. Some guy is making a programming language based on Arabic, called قلب [qlb i.e. qalab? = heart, core] – here’s an article about it at The Reg.

This pleases me both as a linguist and as a former computer nerd. I wish this project the best of luck.

Caveat: Emptor

It was a schadenfreude moment when I ran across this blog post about how the marketers at Rosetta Stone language-learning software are bad at translating, the other day – because I’d decided I didn’t like Rosetta way back shortly after I’d acquired it. I’d decided I’d wasted my $300 and had forgotten it, basically.

It was a schadenfreude moment when I ran across this blog post about how the marketers at Rosetta Stone language-learning software are bad at translating, the other day – because I’d decided I didn’t like Rosetta way back shortly after I’d acquired it. I’d decided I’d wasted my $300 and had forgotten it, basically.

Apparently, the marketers were putting German or Dutch or Swedish noun forms in place of the English verb form for “snow” in a multilingual play-on-words based on the song line “Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow.” Which, of course, indicates a rather poor apprehension of the grammatical issues at play. But then there was a comment on the blog post that made me reconsider, and decide that the criticism of the Rosetta marketers was irrelevant: the commenter (who went by Breffni) wrote:

I don’t get the idea that mixing English with German, Swedish and Dutch is an acceptable conceit, but using nouns for verbs is an incongruity too far. ‘Let it Schnee’ is wrong, all wrong – but ‘Let it schneien’, that would be fine? It’s bilingual word-play, from start to finish.

And so, my schadenfreude moment quickly faded. Because… here’s the thing: I totally agree with this point – if you’re going to play with mixing languages, what does it matter whether you’re getting the grammar right – it’s like complaining that the pieces don’t go together when playing with Legos and Lincoln Logs at the same time (which I did as a child, and I’m sure there are more contemporary equivalents). The point is, you’re mixing things up, so just go with it. That’s what makes it “playing with language,” and not, say, Chomsky’s “government and binding” theory or abstract grammar. In fact, it’s the over-emphasis on grammar vis-a-vis communicative efficacy that I dislike about Rosetta, and thus internet grammar peevers are criticizing from the wrong end, as far as I’m concerned.

So regardless, that doesn’t change the fact that I deeply resent having wasted $300 on Rosetta. But I’m not blaming the marketers. I’m blaming the designers’ poor grasp of foreign-language pedagogy and methodology. The only thing the marketers did wrong was successfully convince me to shell out $300.

Caveat emptor.

Caveat: Timor mortis conturbat me

I that in heill wes and gladnes,

Am trublit now with gret seiknes,

And feblit with infermite;

Timor mortis conturbat me.Our plesance heir is all vane glory,

This fals warld is bot transitory,

The flesche is brukle, the Fend is sle;

Timor mortis conturbat me.The stait of man dois change and vary,

Now sound, now seik, now blith, now sary,

Now dansand mery, now like to dee;

Timor mortis conturbat me.No stait in erd heir standis sickir;

As with the wynd wavis the wickir,

Wavis this warldis vanite.

Timor mortis conturbat me.

Above is excerpt (first 16 lines) from “Lament for the Makers” by William Dunbar, who lived 1456-1513. The Latin, “Timor mortis conturbat me,” means “Fear of death disturbs me.”

The picture below is “Parable of the Blind” by Bruegel the Elder (1568).

Caveat: Dissolving

OK.

<rant>

I’m feeling pretty frustrated and even angry, the last few days. I guess hoesik (business dinner) brings it out, slightly. But it’s not like you would think. What’s got me frustrated and angry? My inability to understand what the heck is going on around me. That’s the language issue.

It’s not even a cultural problem – less and less am I of the opinion that the alleged Korean “communication taboo” that I’ve ranted about before is a real thing – it really boils down to certain naive conceptions of how language works, especially in communities of mixed-ability adults with multiple native languages (by this I mean e.g. there are native Korean speakers with lousy English. native Korean speakers with good English, native English speakers with lousy Korean, and native English speakers with good Korean, in an ideal mixed-ability community). In a work environment, an immense amount of communication takes place that is not explicit: people know what’s going on not because they are directly told, but because they “overhear” what’s going on. It enters their background consciousness. But with my limited and lousy Korean, I miss out on that channel. And then it feels like I’m being singled out for “noncommunication” because I don’t know what’s going on. It’s an artefact of my situation.

The solution is to get better at Korean. Argh. No comment. I’m trying. Really. But obviously, not with a great deal of success. I think my coworkers are deceived that I am better than I am, because I sometimes pick up on things quite easily. But other times, I have literally zero idea. It’s a limitation of adequate vocabulary, more than anything else.

So there. I get frustrated in social situations, which make them stressful for me.

I get frustrated at work, because I have no idea what’s going on, and no one will tell me when I ask – they are too busy, or they don’t know themselves.

I’m frustrated when I try to study, because I feel stupid and inadequate. I guess on the bright side, I have a lot of sympathy for my most boneheaded students – I’m one of them.

But I’m so depressed with this whole situation, lately, that I’m on the verge of tears.

</rant>

OK.

I came home in the cold and made a big bowl of “Spanish rice” with my leftover rice. It’s not really Spanish. It’s just rice with a vaguely Italian-style vegetable and tomato-based sauce added to it.

What I’m listening to right now.

Massive Attack, “Dissolved Girl.”

Caveat: Reduplication

Here are some more examples of reduplicative (or semi-reduplicative) phenomimes and/or psychomimes that I recently ran across. I’ve written about them before (twice).

I’ve given up trying to determine which are technically phenomimes and which are technically psychomimes – the boundary between them seems awfully fuzzy. I suspect things dealing with mood and feeling should be called psychomimes and those dealing with taste (such as most of those below) should be called phenomimes. But aren’t tastes feelings, too? (The -하다 [-hada] are just the verbal-making suffix).

- 섭섭(-하다) [seopseop] = to be disappointed, to be sad

- 새콤달콤(-하다) [saekomdalkom] = to be sweet and sour

- 쫄깃쫄깃(-하다) [jjolgitjjolgit] = to be chewy

- 바삭바삭(-하다) [basakbasak] = to be crispy

- 아삭아사(-하다) [asakasak] = to be crunchy

- 살살 [salsal] = softly

[Update (2015-10-08): I decided to create a consolidated list of examples, which I can update periodically.]

Caveat: impressed by his rhodomontade

I have been reading a book, I Am a Cat, by Soseki Natsume. In translation, of course – I can’t read Japanese – I can barely remember my kana.

I have been reading a book, I Am a Cat, by Soseki Natsume. In translation, of course – I can’t read Japanese – I can barely remember my kana.

I came across a passage that featured the word rhodomontade, which I had never seen before.

Blacky [another cat], like all true braggarts, is somewhat weak in the head. As long as you purr and listen attentively, pretending to be impressed by his rhodomontade, he is a more or less manageable cat.

I had no idea what rhodomontade meant. I looked it up, and lo and behold, it’s from Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (and the antecedant Orlando Innamorato by Boiardo). I supposedly read this work as part of my master’s degree program, and though I could talk about its cultural impact, I suspect I never really made it through the text – my ability in 16th century century Italian wasn’t the best, either – much less now.

When a translation features such an obscure word, it’s an indication of either a poor quality translation or a masterful one. Based on my progress so far through Aiko Ito and Graeme Wilson’s translation of Natsume’s novel (original 吾輩は猫である [Wagahai wa neko de aru]), I’m inclined to believe the latter. It’s an interesting picture of Meiji-era Japan – a period which has always fascinated me in any event.

Or l’alta fantasia, ch’un sentier solo non vuol ch’i’segua ognor, quindi mi guida, e mi ritorna ove il moresco stuolo assorda di rumor Francia e di grida, d’intorno il padiglione ove il figliuolo del re Troiano il santo Impero sfida, e Rodomonte audace se gli vanta arder Parigi e spianar Roma santa. – Orlando Furioso, Canto LXV.

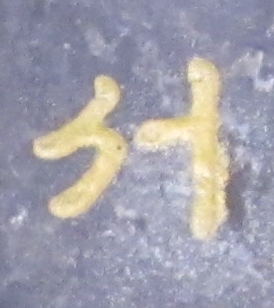

Caveat: Mysterious Squiggle Jamo

When I went to the museum last weekend, I saw a strange jamo.

<digression>

Most of you will say, what’s a jamo? A jamo is a single letter of the Korean alphabet, which is called hangeul (or hangul, if you don’t like to follow official romanization rules and want to just wing it, transliteration-wise, or hangle, if you’re a 5th grader with a seussian penchant). So, for example, ㅅ is a jamo. Or ㅎ is a jamo – my favorite, because it looks like a little man with a hat. The jamo are gathered together to make blocks (모아쓰기 = gather [and] writing), so ㅎ + ㅏ + ㄴ becomes 한.

</digression>

The jamo I saw was the one on the left in this image:

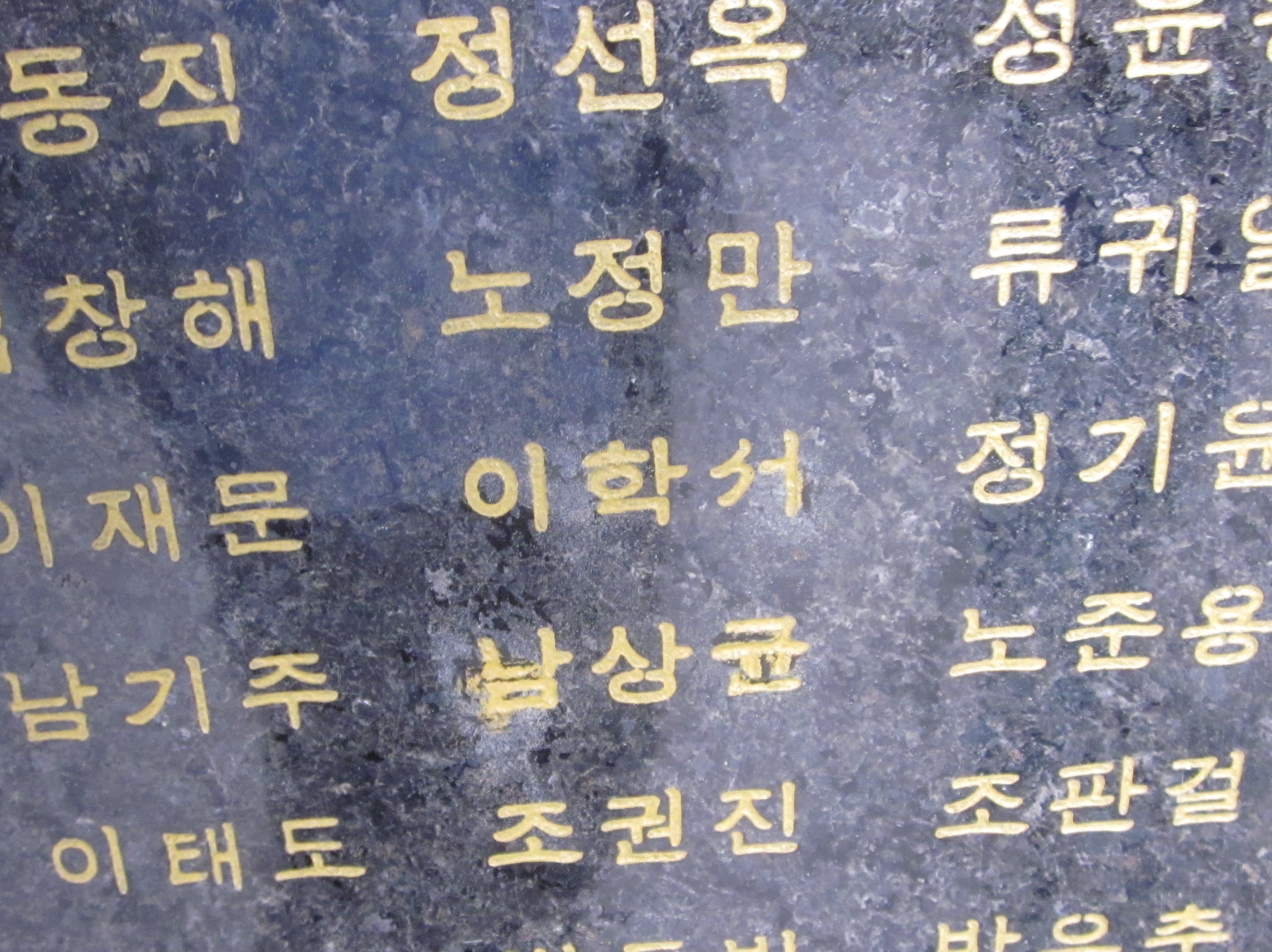

Which is extracted from this monument of names of deceased soldiers from the Korean war (squiggle jamo found in center):

The mysterious squiggle jamo is not one that is taught when learning Korean, so I wondered what it was. It’s very hard to research. When I tried to take the image above and do a ‘google image search’ I just got pictures of naked people in strange positions – so much for google.

And good luck trying to search a term like “mysterious squiggle jamo” – perhaps now that I’m blogging this, future mystified foreigners will be less stumped.

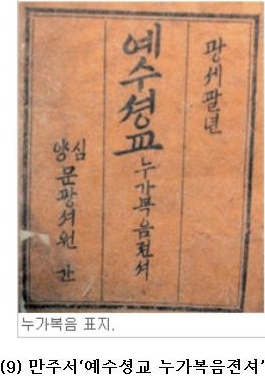

OK, so, conclusions, after extensive searching? The squiggle jamo is an alternate ‘s’ (i.e. the jamo ㅅ). My friend Curt assured me it was. And I finally found something where the squiggle jamo is clearly transcribed as ㅅ- it’s the cover of an 1880s New Testament (note that in 1880s using hangeul, as opposed to Chinese script, was pretty radical).

The large characters are clearly transcribed below as 예수셩교, with the squiggle jamo in the 셩 (an old spelling of 성 = ‘saint, holy’). So now that I have seen the internet says so, it must be true.

Caveat: 망했다

I have a student who says this one phrase all the time. It seemed to indicate a kind of fatalistic and pained attitude with respect to assignments, tasks, homework, etc., as today when she took a look at a page of “paraphrasing” exercises we were working on and exclaimed “망했다” [mang-haet-da]. Finally, I broke down and asked, what does this mean. She said without pause, “ruin.” This was funny, but I suspected it wasn’t a very good translation.

Some research shows that the underlying verb, 망하다, does include a meaning of “ruin,” as well as “perish, die out, destroy, go bankrupt, crash” as well as “to be ugly, to be unbecoming.” But the googletranslate also gave me a hint when I found one fixed expression where the verb, with a slightly different ending, was translated as “damn.” In an online dictionary, I had found the example phrase “망할지 오랫동안 살아남을지 누가 알겠는가?” which is given with the translation “Who knows if it may sink or swim in the long run?” But the same Korean phrase in googletranslate gives “Long damn that would survive, who knows?” – which is undeniably utter nonsense, like most of googletranslate’s output – but it nevertheless provided that “damn” as a clue.

As a result of this research, combined with the evident usage by my student, I’ve decided that the pragmatics of the phrase are essentially, “Damn!” or perhaps “Crash and burn!” as it was used in certain programming circles I worked in, when some task was essentially impossible.

In any event, I like the phrase. Perhaps I’ll try to be brave and use it at the appropriate moment, sometime.

I finally used another phrase today that I’ve been hearing for ages and understood the pragmatics of, but which intimidated me because of how disconnected its literal meaning was from its pragmatics: 들어가겠습니다. The pragmatics seem to be, “take care,” in the way we use that phrase to say “good bye” in a familiar way. But the literal meaning of the underlying phrasal verb, 들어가다 is “to enter.” How does saying, “[I] will enter” end up meaning “good bye”?

Enter what? I’d like to know. One coworker explained, somewhat brokenly, that there’s an elided, never-stated, “my home” home in the phrase: “I will enter my home now.” I suspect it’s a little bit like Mexicans saying “andale” which literally means “walk on it,” but has the pragmatics of “that’s right,” or even “take care.”

But I used it and everyone just said other similar good-bye noises in an utterly unremarkable way. It works. Language is weird.

Caveat: शिला

There is a philosopher named Justin E. H. Smith whose blog I sometimes read. Lately, he’s been studying Sanskrit, and so he recently wrote a composition in Sanskrit. I can’t read Sanskrit – I studied it for a few weeks a few decades ago, and I can barely even remember how to decipher the writing system. But I can sympathize with and relate to the idea of trying to write an interesting or creative composition in a language one is only just beginning to master – consider a few of the horribly bad and embarrassingly juvenile efforts I’ve made at putting up blog posts in Korean (which I won’t even link to here, because I’m too embarrassed).

There is a philosopher named Justin E. H. Smith whose blog I sometimes read. Lately, he’s been studying Sanskrit, and so he recently wrote a composition in Sanskrit. I can’t read Sanskrit – I studied it for a few weeks a few decades ago, and I can barely even remember how to decipher the writing system. But I can sympathize with and relate to the idea of trying to write an interesting or creative composition in a language one is only just beginning to master – consider a few of the horribly bad and embarrassingly juvenile efforts I’ve made at putting up blog posts in Korean (which I won’t even link to here, because I’m too embarrassed).

But in fact, in reading his translation back to English of his Sanskrit composition, I got to thinking. The composition – his little parable of the stone – is excellent. As is so often the case, operating within very tight constraints can lead to very good writing – in this case, the constraint of working in a language one doesn’t know well. I can’t judge the quality of the Sanskrit – perhaps it’s full of grammatical errors or mis-used vocabulary. But the English version is compelling. I will reproduce it here.

शिला

एकदासित् शिला । एतायाः शिलायाः पदाः न सन्ति स्म, न नेत्रेपि, न श्रवने, न लोमचर्मनम्, न वदनम् । शिला गन्तुं न शक्नोति स्म, प्रानितुं न शक्नोति स्म, खदितुं न शक्नोति स्म, न किं अपि कर्तुं शक्नोति स्म । परन्तु एतायाः शिलायाः जिवात्मन् अस्ति स्म । सातिवाकुशलिन्यासित् । एक्स्मिन् दिने पक्शिनि शिलायायाम् उपविशति स्म । पक्शिनि झटित्यनुभवत् यत् शिला जिवितासित् । सोक्तवति : “भो शिला” इति, “तव किं अभवत् । शिलाः केवलम् अजिवनि वस्तुनि सन्ति” । शिला प्रत्युक्तोवति : “धिक् ! अहं न जानामि किं मम अभवत् । अहं शिलास्मि । गन्तुं न शकनोमि । प्रानितुं न शक्नोमि । खदितुं न शक्नोमि । न किं चित् कर्तुं न शक्नोमि । अहं केवलम् वस्तुवस्मि । मया न जीतव्यम् । न जानामि अपि कुतः अहं विशयः एतायाः कथायाः अस्मि” इति । पक्शिनि उक्तोवति : “तद्विशये चिन्ता मस्तु । गन्तुं नातिव सु्नदरम् अस्ति । अहं च नितरम् बुबुक्शास्मि । तव जीवनम् सुलभम् अस्ति । त्वया केवलम् चिन्तयितव्यम् च ध्यनम् कर्तव्यम् च । भूमिः तव भार्यास्ति । चिन्तनम् तव भोजनम् अस्ति । सुन्दरम् एतत् जिवनम्” इति । एतैः शब्दैः पक्शिनि समुत्पतति स्म । शिला पुन एककिन्यासित् । कुशलिन्यासित् । सा तस्या भार्याम् अलिन्गति स्म च भोजनम् खदति स्म च । भक्शणम् कृत्वा प्रस्वपिति स्म च स्वपनम् पक्शगमस्य विशये करोति स्म च ।

The Stone

Once there was a stone. This stone had no feet, no eyes, no ears, fur, or face. It could not move, could not breath, could not eat, could not do anything at all. But this stone had a soul. It was very unhappy. One day a bird landed on it. The bird immediately sensed that the stone was alive. It said: “Hey, stone! What’s with you? Stones are only non-living things.” The stone replied: “What a pity! I don’t know what’s with me. I am a stone. I cannot move. I cannot breath. I cannot eat. I cannot do anything at all. I am only a thing. It is not for me to live. I do not even know why I am the subject of this story.” The bird said: “Don’t worry about it. Moving is not so wonderful. And I’m always hungry. Your life is easy. You just have to think and meditate. The earth is your wife. Thoughts are your food. What a nice life.” With these words the bird flew away. The stone was again alone. It was happy. It embraced its wife and had a meal. Having eaten, it went to sleep and dreamt of flying.

Caveat: Not Swedish

I recently saw an article on The Atlantic that explained that the muppet known as the Swedish Chef does not, in fact, speak Swedish. Well, of course not. But that hasn’t stopped some Swedish guy from “transcribing” his talk. Sample:

[UPDATE: sadly this video has disappeared. No replacement can be found. Yay internet!]

I like it mostly for the linguistic aspect. But he’s kind of funny, too – especially the turtle.

Caveat: Bob Knob’s Daddy-O

Someone attempted to comment on a recent blog entry of mine – the one about PSY’s “Gangnam Style” song. The commenter was what I would I consider a troll – mostly by virtue of the fact that he (or she, but I suspect he, since he called himself Bob Knob – a very troll-like name, too) declined to provide a means for contacting him (i.e. the email address provided was invalid).

Because of the troll-like nature of the comment, I didn’t approve it. Yet I feel compelled to address his criticism, which struck me as nevertheless having some validity. Here is what Bob Knob wrote:

Ehhh… 오빠 (oppa) is what young Korean girls call guys that are slightly

older, in particular their boyfriends. The literal translation is “big

brother” (but guys don’t use it to refer to their older brothers), so

“Daddy-O” isn’t all that accurate.

First and foremost: duh. I know what 오빠 [oppa] means. I suspect that Bob Knob doesn’t know what ‘Daddy-O’ means. ‘Oppa’ literally means a woman’s older brother, but it’s used to address older men affectionately and also (and this is important) it’s used to address boyfriends. Daddy-O is not really current American slang, but in the 1960s it meant someone in authority but who was being addressed informally, and it also was used by some “hip” women to refer to their boyfriends. I seem to remember seeing it a lot as a form address between prostitutes and clients (and or pimps) during a particular epoch, too.

The term ‘Daddy-O’ thus means “informal flirtatious term of address directed by a woman toward a man, with vaguely incestuous connotations.” Which is exactly how I would define ‘oppa,’ too.

In that way, by translating ‘oppa’ as ‘daddy-o’ I try to capture that same semantic field (since in Anglophone culture there is nothing that resembles calling a boyfriend “brother”); but also, because the term ‘oppa’ is clearly being used somewhat ironically (same as the ‘manly man’) in the song in reference to the middle aged man singing it, I figured using an out-of-date slang term like daddy-o would serve that purpose well.

I was tempted to use the term ‘papi’ which is used in hispanic culture to address older men and espeically boyfriends – ‘oppa’ works similarly in Korean culture.

Well, anyway. I doubt the troll named Bob Knob will read this, but I felt compelled to respond with this cultural/linguistic observation. I should also note that this same “Gangnam Style” video has gone sufficiently viral in the US that there’s an extensive write-up about it at one of my favorite US news websites, The Atlantic. Max Fisher, the article’s author, himself pointed to an extensive write up by Jea Kim at her blog My Dear Korea (a blog which looks interesting enough in general to be someplace I may return to regularly). She further returns with a comment on Fisher’s article, in which she takes issue with just how revolutionary the video’s satire is – and in that, I’m inclined to agree with her – to see the video as revolutionary in a Korean context is to be rather myopic vis-a-vis Korean cultural history.

I’ll conclude with this fascinating bit of Americana. Watch it through to the end for some original Daddy-Os.

Caveat: Invective!

My TP2 class was in high spirits. Two of them were arguing. They slipped between Korean and English.

One student said of another, "He said invective to me!"

"Invective!" the other said.

"See? Abuse. Abuse. Oh, he is not kind."

What was funny was that what he was saying was literally just "invective" (and I think words in the vein of "욕설" [yokseol] which mean "abuse, invective"). This is "meta" language – he wasn't actually uttering abusive language, he was just uttering pointers to abusive language. This was weirdly clever and strange to see played out.

[Daily log: walking, 3 km]

Caveat: Macaronic

“Macaronic” means a text that mixes languages for comedic effect. It’s deliberate, pun-based code-switching, in linguistics terms. My students do it, when they hear English that “sounds funny” to them in their Korean ears, and they will suddenly start repeating some random word or phrase that I’ve said and laughing, no doubt because it sounds like something in Korean that’s funny. I can’t think of an example at the moment, but I have these moments constantly in my classes.

I ran across a macaronic poem mixing Latin and English while browsing the Language Log blog – a commenter had posted a poem by A.D. Godley entitled “Motor Bus” to an original posting about the syllabuses/syllabi debate. It’s a play on the fact that “motor” and “bus” are both words of Latin origin (although truncated and changed) and therefore they might be required to participate in the complex Latin morphology in a multilingual discussion of motor buses.

What is this that roareth thus?

Can it be a Motor Bus?

Yes, the smell and hideous hum

Indicat Motorem Bum!

Implet in the Corn and High

Terror me Motoris Bi:

Bo Motori clamitabo

Ne Motore caedar a Bo—

Dative be or Ablative

So thou only let us live:—

Whither shall thy victims flee?

Spare us, spare us, Motor Be!

Thus I sang; and still anigh

Came in hordes Motores Bi,

Et complebat omne forum

Copia Motorum Borum.

How shall wretches live like us

Cincti Bis Motoribus?

Domine, defende nos

Contra hos Motores Bos!

Caveat: 빈정상했어

At work yesterday, the front-desk person was handing out some student-placement spreadsheet printouts and she skipped me. This always annoys me, because I have a genuine interest in what’s happening to the students.

I think they leave me out because they assume I’m not interested, since I don’t often don’t join in the discussions they have over these printouts (given that they are in Korean and/or they often seem to take place at times when I’m off teaching a class – my schedule is thicker in the afternoons whereas many of the teachers have a thin afternoon schedule and a thicker evening schedule, and so meetings are often in the afternoons).

So this time, I said something like, “why are you forgetting me, can I have one too?” and she happily complied.

But then Curt remarked, muttering, “빈정상했어” [bin-jeong-sang-haess-eo]. And of course I had no idea what this meant. And I wanted to know.

It therefore became a long, drawn-out discussion over what, exactly, this phrase means. The verb (빈정상하다 [binjeongsanghada] / alternate form 빈정사다 [binjeongsada]) doesn’t appear any online Korean-English dictionaries we consulted. Google translate doesn’t even try.

After some back-and-forth, we decided it meant something roughly like “peeve” as in, “he’s/you’re peeved” (the subject is left out in Korean and so you can fill in whatever verb subject fits the situation). But I wasn’t really satisfied with this.

The Korean-Korean dictionaries online don’t have the verb (or the pre-derived verb-noun 빈정상) either. For the near-match 비정상, they offer definitions as follows. The definitions are hard enough to understand – my “translations” of the definitions are tentative at best.

1.) 어떤 것이 바뀌어 달라지거나 탈이 생겨 나타나는 제대로가 아닌 상태. “The condition of [something] not being as one desires [such] that some kind of trouble or revised change appears.”

2.) 바르거나 떳떳하지 못한 상태. “The condition of being unable to be honorable or upright.”

These definitions utterly fail to match Curt’s off-the-cuff definition and don’t match my intuition of verb’s actual meaning. They don’t make any sense at all, in my opinion. So that’s not it. Just a lexical wild-goose-chase.

Looking at the verb in parts (which isn’t always a smart or correct thing to do with Korean verbs, as my Korean tutor is constantly insisting), I see the first part is 빈정, which appears bound in other verbs like 빈정거리다, which means “to make a sarcastic remark.” And the second part is 상하다, which includes a definition “to be hurt, to be offended, to be troubled with.” This latter is promising – it seems to match Curt’s definition much better. If you add in a shading of sarcasm, it actually seems to capture my actual expression and manner pretty well.

Looking at the verb in parts (which isn’t always a smart or correct thing to do with Korean verbs, as my Korean tutor is constantly insisting), I see the first part is 빈정, which appears bound in other verbs like 빈정거리다, which means “to make a sarcastic remark.” And the second part is 상하다, which includes a definition “to be hurt, to be offended, to be troubled with.” This latter is promising – it seems to match Curt’s definition much better. If you add in a shading of sarcasm, it actually seems to capture my actual expression and manner pretty well.

So I’m going to offer a tentative English definition of the phrase “빈정상했어” as “he’s/you’re sarcastically peeved” … but in slangy pragmatics (and dating myself to the 1980s) as “don’t have a cow, man.”

What I’m listening to right now.

Linkin Park, “Pushing Me Away.”

Caveat: The Future Behind Us

When talking about the future, I gesture to my front. When talking about the past, I gesture to my back. Over the last several years of teaching English in Korea, I've become aware that this may not be a human universal, but rather, something dependant on my Western cultural background.

I don't really know what the "rule" is, in Korea, about whether the future is in front of you or behind you, but I've gradually come to suspect it might not be exactly as in Western culture. Recently, I ran across something that hints at the possibility of difference – not with respect to Korean culture specifically, but with respect to language and/or cultural universals. A quote (hat tip to Sullyblog):

Patterns in spatio-temporal metaphors have also revealed striking reversals of the direction of time. For example, in languages like English and Spanish spatial metaphors put the past behind the observer (e.g., the worst is already behind us) and the future in front (e.g., the best is still ahead of us). In Aymara [a Peruvian native American language], this pattern is reversed and future is said to be behind the observer while the past is in front. This pattern in metaphors is reflected in patterns in spontaneous co-speech gesture. When talking about the past, the Aymara gesture in front of them, and when talking about the future, they gesture behind them, a striking reversal from patterns observed with speakers of English or Spanish.

I'm going to have to watch Koreans closely for those "spontaneous co-speech gestures." I have some suspicion (which may be false) that I might find a different conceptualization of time, which has been hinted at by the difficulties I've occasionally had with using gesture to convey the meanings of past and future (which, in an EFL classroom, come up in a discussion of verb tenses, among other things). More on time spatial metaphors here.

Caveat: Caught Hypocrisizing

Well, not severely, but it was a bit hypocritical of me to criticize Martin’s unforgiving Yale-fication of the Korean language (as I did, originally, here), and then commit the opposite sin of failing to provide transliterations for those who might not be comfortable reading hangeul. Shame on me – I’m a lazy linguist, too.

This was brought to my attention by my friend Bob, who commented on a recent entry of mine about phenomimes and psychomimes (his comment is attached to that entry). So I have gone back and revised that entry to include transliterations using the revised SK government standard for romanization.

He also wonders about the difference between phenomimes and psychomimes. I’m a little vague on that, myself, but of those listed in the previous entry, I would hazard to say that maybe 살금살금 [san-geum-san-geum = sneakily] borders on psychomime territory, since it conveys an attitude more than a phenomenon. The difference is hardly clear, to me. But I would look to that kind of thinking as the criteria.

Caveat: 의성어와 의태어

의성어 [ui-seong-eo] is phonomime, which is to say, an onomatopoeic word, a word that imitates a sound. 의태어 [ui-tae-eo] is phenomime, which differs in that it’s a kind of “sound symbolism” of a feeling rather than an imitative representation. I’ve written about these things before: see here. One of the most common google search terms that brings internauts to my blog randomly is “phenomimes and psychomimes.”

I’ll admit, these things fascinate me. I frequently revisit them. I found a very brief one page pdf summary of them, this morning. And there’s a chapter in Samuel E. Martin’s exhaustive and exhaustingly Yale-ified Korean grammar about them, too (p. 340~344).

I’ll reproduce some interesting vocabulary.

… some phonomimes:

추룩 추루룩 추루룩 [chu-ruk chu-ru-ruk chu-ru-ruk] = downpouringly

보글보글 [bo-geul-bo-geul] / 바글바글 [ba-geul-ba-geul] / 부글부글 [bu-geul-bu-geul] / 뽀글뽀글 [ppo-geul-ppo-geul] / 빠글빠글 [ppa-geul-ppa-geul] / 뿌글뿌글 [ppu-geul-ppu-geul] = boilingly, bubblingly

찰랑찰랑 [chal-lang-chal-lang] / 출렁출렁 [chul-leong-chul-leong] / etc. = lappingly, sloppingly

꽹구랑 꽹꽹깽 [kkwaeng-gu-rang kkwaeng-kkwaeng-kkaeng] = gongingly

… and some phenomimes:

살금살금 [sal-geum-sal-geum] = sneakily

깡충깡충 [kkang-chung-kkang-chung] = bouncily, “hoppingly” (also 깡총깡총[kkang-chong-kkang-chong])

말똥말똥 [mal-ttong-mal-ttong] / 멀뚱멀뚱 [meol-ttung-meol-ttung] = wide-eyed staringly

말랑 몰랑 물렁 [mal-lang mol-lang mul-leong] / 말캉 몰캉 물캉 [mal-kang mol-kang mul-kang] = softly / tenderly (as a texture of food)

살짝 [sal-jjak] / 설쩍 [seol-jjeok] = stealthily

싱글벙글 [sing-geul-beong-geul] = smilingly

날씬 [nal-ssin] / 늘씬[neul-ssin] = slimly, slenderly

통통 [tong-tong] / 퉁퉁 [tung-tung] = plumply

살살 [sal-sal] / 설설 [seol-seol] / 솔솔 [sol-sol] / 술술 [sul-sul] = gently, softly

싹독 [ssak-dok] / 썩둑 [seok-duk] = choppingly, snippingly

빡빡 [ppak-ppak] / 뼉뼉 [ppeok-ppeok] = crustily, tightly, narrow-mindedly

반짝 [ban-jjak] / 번쩍 [beon-jjeok] / 빤짝 [ppan-jjak] / 뻔쩍 [ppeon-jjeok] = sparklingly, twinklingly

A random picture (2010, Gwangju).

[Update (2015-10-08): I decided to create a consolidated list of examples, which I can update periodically.]

![]()

Caveat: TLIs not TLAs

How is it at all possible that I reached the age of 46 without realizing that there are pedants out there who like to distinguish between the concepts of acronym (a pronounciable grouping of first letters and sounds, e.g. NASA) and initialism (an unpronounciable grouping of first letters, e.g. FBI)? And to think that I was a literature major!

According to the wiktionary, there are 3 meanings for acronym:

1. An abbreviation formed by (usually initial) letters taken from a word or series of words, that is itself pronounced as a word, such as RAM, radar, or scuba; sometimes contrasted with initialism.

2. A pronounceable word formed from the beginnings (letter or syllable) of other words and thus representing the phrase so formed, e.g. Benelux = the countries Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg considered as a political or economic whole.

3. Any abbreviation so formed, regardless of pronunciation, such as TNT, IBM, or XML.

I always, always thought that definition 3 was the main definition. For me, it was the only definition. But a usage note says, “The third sense is often criticized by commentators who prefer the term initialism for abbreviations that are not pronounced like an ordinary word.” So it turns out that these anonymous commentators would have judged me to be wrong, all these years.

My absolute favorite acronym, therefore, turns out to actually be an initialism (unless you are good at pronouncing the /tl/ cluster, as in the Nahuatl language): TLA = three-letter acronym. Properly speaking, it should instead be TLI = three-letter initialism. Somehow, it seems less compelling, that way. But that’s just because it shakes up my long-held habit. I’ll try to adapt.

Here’s a lingering question, however. Some potential acronyms are nevertheless typically “pronounced” as initialisms. Anyone could say /ukla/ for UCLA, if they wanted (and, in fact, Spanish speakers generally do exactly that, for example), but people typically spell it out in English, U.C.L.A. So is it an acronym or an initialism?

What I’m listening to right now.

Cat Stevens (AKA Yusuf Islam), “My Lady d’Arbanville.” He looks so very 70’s in that video.

Cat Stevens (AKA Yusuf Islam), “My Lady d’Arbanville.” He looks so very 70’s in that video.

But I’ve been realizing, when I heard it came around on the mp3 shuffle… Cat Stevens has been more consistently a part of my “life soundtrack” than any other composer or singer in my life – he was part of my parents’ soundtrack when I was child growing up, he was a major component of my own listening, as an adolescent, and unlike other musical manias and fads I’ve had, he’s always been on the short rotation. If I had to guess a single album that I’ve listened to more times than any other, it would almost undoubtedly be Mona Bone Jakon (the disturbing origin of this album title is slightly NSFW – interestingly, this latter term is an acronym [pardon me, initialism] which was being written about by Alan Jacobs at the Atlantic wherein I first learned of this aforementioned acronym/initialism distinction – thus, full circle).

Caveat: Enough about Stella, Already!

I went to an accent-study survey (referenced from Language Log) in which many different speakers of English (mostly non native but with a few native speakers thrown in) read a passage – something about Stella shopping for peas and blue cheese and a toy frog. It gets kind of repetitive, and I concluded that the survey was badly designed. Here's the comment I posted at Language Log regarding my experience trying the survey.

I went through the survey fairly confidently, even naively, before reading these comments. And then I read Sarah Taub's: "I think my problem is that I wanted to interpret the study as asking how much the speakers sounded like native English speakers. I wish I had had more guidance from the experimenter as to how important the "native vs. non-native" and "US English vs. foreign" dimensions were. Perhaps those two dimensions should not have been combined in one experimental set."

Now I'm second-guessing myself. I really had no idea how to balance these two aspects, and I agree with her comment that they should have provided more guidance on separating the two dimensions: native vs non-native and American vs non-American. What I ended up doing was essentially rating them on strictly the native vs non-native dimension (because I've spent too much of my life outside the US, perhaps, to actually CARE about the US vs non-US dimension?). So I gave a lot of scores in the 4 to 6 range (as an ESL teacher I am perhaps too generous – if I can understand them then they don't sound THAT foreign – "foreign" is when you really actually can't even make out what they are talking about!). And then, if someone was a 6, I awarded a 7 to those who were unambiguously American-sounding to me – which was exactly two.

Despite my frustration with the survey, I have a nearly inexhaustible patience with and fascination for these types of things. I really should go back to graduate school, shouldn't I? In linguistics, I mean…

Caveat: Coneix l’ala la tristesa dels núvols de seda

LA CIUTAT DE LA TARDOR

Et vull

color de rosa en la tardor

– Betül TarimanConeix l’ala la tristesa dels núvols de seda,

les fulles dels ocells que niuen a les moreres

de l’avinguda del dolor.

Sap de la tempesta i el devessall de les aigües

l’aiguavessant de l’espill bombejat per la febre de l’alba,

l’argent viu de tots els desvaris del termòmetre

dels amors vells.

La tristesa: “en la cara de la mort tot es veu”

Els meus ulls s’han rentat en els teus

La meua sang s’ha mudat al teu cor,

però mai no m’arribarà la llum a la boira.– Pere Bessó, de "Aigües turques", 2010

Poesía en catalán. Encontrado aquí (con traducción al español). Al azar, encontré una red de sitios algo prolífica que exploraba durante varias horas. Valdrá la pena volver.

Con la excepción de esas horas perdidas, pasaba mi domingo fuera del internet. A pesar de la primavera, he sentido un ligero cansansio. Pues no hice nada.

[Daily log: walking, 1 km]

Caveat: All Your Bad Englishes Are Belong to Us

Actually, I LOVE bad Englishes. As a descriptive linguist, I don't feel any need to correct them, when they memify. Rather, I feel a strong temptation to encourage their proliferation – because it's like I want to encourage linguistic diversity and language change. Well, anyway, there was a posting at Language Log about the "All Your Base" meme, and I was thinking about it.

What I'm listening to right now.

All Your Base Are Belong To Us – Youtube fan-techno, or something. Right. 물론!

Relatedly, while surfing the decrepit and latent links of LanguageLogLand, I ran across the most romantic nerd-poem EVER:

roses are #FF0000

violets are #0000FF

all my base

are belong to you

Caveat: please refrain from making love excessively

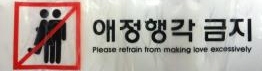

I ran across the following sticker recently.

The English translation in smaller letters is quite alarming. It says: “please refrain from making love excessively.” This seems R-Rated, and not the sort of thing a kid should have on a backpack.

But the Korean isn’t really that strongly worded. What it says is “애정행각금지.” A brief internet search and/or dictionary quest reveals that “애정행각” basically just means what Americans call PDA – “Public Displays of Affection.” So with the “금지” tacked on, a much better (and milder) translation would be “PDA Prohibitted.” This is much more G-Rated, and could even be imagined to be posted in a park or school or church. I think the point of the sticker is a little bit ironic. But with the atrocious English translation, it goes from irony to downright weird pretty quickly.

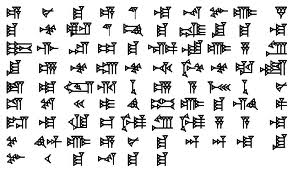

Caveat: Recordings in Akkadian

It turns out that some professors of ancient, extinct languages such as Babylonian, Assyrian and Akkadian (which are all related to each other and to modern Arabic and Hebrew) have decided to make voice recordings of Mesopotamian literature (including Gilgamesh!). These recordings are hosted at the University of Cambridge, here. I’m weird: I like this. I listen to them… without understanding them.

It turns out that some professors of ancient, extinct languages such as Babylonian, Assyrian and Akkadian (which are all related to each other and to modern Arabic and Hebrew) have decided to make voice recordings of Mesopotamian literature (including Gilgamesh!). These recordings are hosted at the University of Cambridge, here. I’m weird: I like this. I listen to them… without understanding them.

Meanwhile, I’ve been regretting the fact that I kind of dropped the ball on my efforts to develop an exercise routine, last fall. So starting today, I’m going to post a “daily log” as a footnote to my evening blog-post. Such as it were. I walked around part of the lake at the park, this evening, after work.

[Daily log: walking, 7 km; running, 1 km]

Caveat: ¿qué piense Ud?

This academic paper is potentially interesting, but I can't really say, since it's behind a paywall. Here's the abstract, in full:

Would you make the same decisions in a foreign language as you would in your native tongue? It may be intuitive that people would make the same choices regardless of the language they are using, or that the difficulty of using a foreign language would make decisions less systematic. We discovered, however, that the opposite is true: Using a foreign language reduces decision-making biases. Four experiments show that the framing effect disappears when choices are presented in a foreign tongue. Whereas people were risk averse for gains and risk seeking for losses when choices were presented in their native tongue, they were not influenced by this framing manipulation in a foreign language. Two additional experiments show that using a foreign language reduces loss aversion, increasing the acceptance of both hypothetical and real bets with positive expected value. We propose that these effects arise because a foreign language provides greater cognitive and emotional distance than a native tongue does.

I have some questions. How is "thinking in a foreign language" defined? If you're thinking in it, how is it foreign? What about native bilinguals?

Caveat: Kamyk

Kamyk

– Zbigniew Herbertkamyk jest stworzeniem

doskonałymrówny samemu sobie

pilnujący swych granicwypełniony dokładnie

kamiennym sensemo zapachu który niczego nie przypomina

niczego nie płoszy nie budzi pożądaniajego zapał i chłód

są słuszne i pełne godnościczuję ciężki wyrzut

kiedy go trzymam w dłoni

i ciało jego szlachetne

przenika fałszywe ciepło—Kamyki nie dają się oswoić

do końca będą na nas patrzeć

okiem spokojnym bardzo jasnym

The poem is in Polish. Several translations are circulating – following, here’s one from from a website called Pacze Moj (it’s quite unclear to me if Pacze Moj is also a person, or if it’s a pseudonym, or if it’s just a blog title – my Polish is quite bad to the point of nonexistent).

Pebble

by Zbigniew HerbertThe pebble is a creature,

ideal,a self equal to itself,

guarding its own borders,filled precisely,

with stone pebblessence,with a smell reminiscent of nothing,

It frightens nothing, arouses no desires,its fervour and its cold,

are righteous and dignified,I feel a heavy remorse,

when I hold it in my hand,

and its noble body

is permeated by false warmth,—Pebbles will not be tamed,

till the end they will gaze upon us,

through quiet eye so clear.

I like Polish. Maybe someday…