In the form of various unstructured entries with fairly random thoughts, I’ve been working on this project for several years, and it’s come to have the name “If I Ran The Hagwon” (abbreviated as IIRTHW). This topic seems to be evolving into my first effort at something resembling long-form journalism on my blog. Here is Part III. I posted Parts I and II several months ago. Unlike Parts I and II, this Part III is intended to be an evolving document, because, as I observed in a blog-post dated October 4th, 2013, I keep changing my mind. So… this article is permanently UNFINISHED – please bear that in mind as you read it.

UPDATE: On October 11th, 2013, a hagwon owner who blogs under the name wangjangnim wrote an extended “response” to this list of ideas (appearing simultaneously on his blog and at koreabridge.net). I think overall his response is fair, and I understand his counterpoints and criticisms. Please note, however, that if you are linking to this page from that article, that this is intended to be an evolving document (as pointed out above). Therefore I may introduce edits which alter or revise the points below in such a way as to make wangjangnim’s criticisms incoherent – indeed, I have already begun to revise some of the points to better clarify them in light of his thoughts.

[Part I]

[Part II]

Part III – My Ideal Hagwon

Now that I have established, in the previous two parts, the business context for running an English hagwon in South Korea in this day and age, I want to try to answer the question, what would make a great hagwon?

I have frequently had these “If I Ran The Hagwon” fantasies. I’ll admit, too, that I have been more than a little bit disappointed in the putative “curriculum development” aspect of my current job description – both due to my own failings and and due to the lack of genuine opportunities offered to do so. The constraints on what I can do about the curriculum in my current position at KarmaPlus Academy are even more constrained than under pre-merger Karma Academy, too.

Everything following is strictly based on my own opinions – they’re the things I would do in my hagwon. It is not my intention to exclude other, even contradictory approaches to running a hagwon. I believe very strongly that in a fragmented market, there is room for multiple products.

What comes below, then, is a list of strategies or “ways of business” that I’d like to try. This list began with the previous list I was making on my blog (entries here and here) – the individual ideas have morphed and developed but I have made an effort to retain the numbering of those earlier ideas (1-12), with new ideas added as higher numbers (13+).

Idea 1. (HR.) Weekly English Class for Korean Teachers.

The English language hagwon business has a core mission: teaching English to Korean students. Therefore language competency is at the core of the business. Because of this, I suggest that there should be a program encouraging a constant improvement of language skills on the part of all staff. The non-native-speaking English teachers (Koreans) should improve their English. Korean teachers should have some amount of time set aside each week to study their English, and this should be a compensated additional duty of the English native-speaking teachers to provide instruction.

As a point of observation: this was an actual duty of mine at my public school teaching job. Every week, I had to teach an English lesson to my fellow teachers. Frankly, I believe it’s even more important in a hagwon environment, where quality-of-instruction is paramount. It could be argued that it takes away from time teachers could be teaching or prepping for class, and thus represents an “overhead cost” that has no impact on the bottom line. I think it’s important to differentiate short-term thinking from longer-term thinking, here: are we trying to build an institution with loyal and well-qualified employees, or just trying to pay next month’s bills? I know the fiscal position of a typical Korean hagwon is perilous – but please note the use of the word “Ideal” in the title to this article.

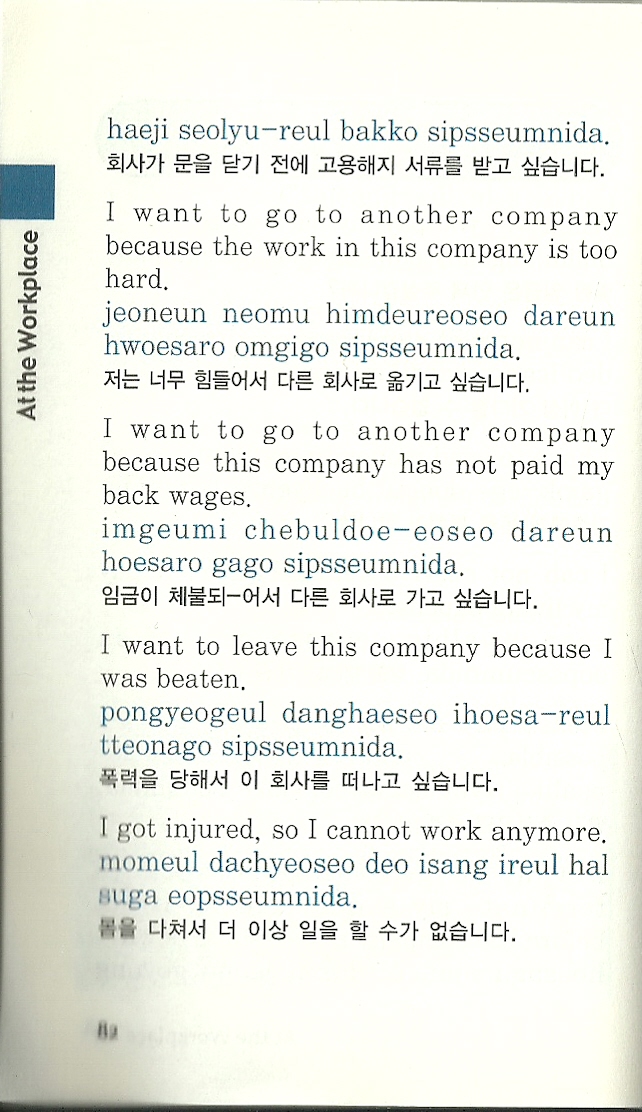

Idea 2. (HR.) Weekly Korean Class for English Teachers.

For the same reason as Idea 1, above, vice versa, non-Korean-speaking teachers (i.e. foreign teachers) should have some amount of time set aside each week to learn Korean, and this should be a compensated additional duty of the Korean-speaking teachers. This functions as a perk for the foreign teachers and a way to get the Korean and foreign teachers interacting, too. It can also provide some awareness of cultural-differences to both sides.

Koreans’ lack of trust and failure to include foreign teachers in team building and decision making ends up being a self-fulfilling prophecy, over time the foreign teachers cease trying to be team members and become unreliable.

Idea 3. (HR.) Full Social Engagement Between Management and Co-Workers.

Management should provide opportunities for colleagues to interact socially and provide incentives for them to do so – foremost, that means being willing to subsidize social events of various kinds. This might seem extravagant, but the “pay off” in team cohesion is significant. Managers should feel obligated to attend certain types of social events of their employees, and should encourage other employees to attend too. Things like weddings, children’s first birthdays, etc., are very important in Korean culture, and by attending these sorts of functions, they’re showing interest in their employees lives. I suspect managers and coworkers avoid these sorts of things (when they do) because of the cost (since small financial contributions are essentially obligatory). For this reason, there should be a discreet gift fund set up to make this possible for managers and employees who want to attend but can’t afford to.

Although one could protest that this kind of thing is “excess” and unnecessary to the core business of a hagwon, in fact half of the hagwon that I have worked at have operated this way. It definitely improves staff morale. Some employees resent contributing to a gift fund, but I have never felt that way, as it all “comes around” anyway.

Idea 4. (HR.) Regular Business Lunches and Dinners and/or Catered Meetings.

For the same reason as Idea 3 (above), group meals should be a regular event, and should be an integral part of the schedule. I really enjoyed eating meals with my bosses and coworkers, when I was working at the first hagwon I worked at in Korea, where we did that several times a week. Although it’s true that business conditions for hagwon were much better in 2007 than more recently, nevertheless I think that the owner’s generosity with staff at that first hagwon I worked at contribed greatly to the fact that it was also, arguably, the most successful hagwon I’ve worked at. I also remember learning a lot about my coworkers and my job when I would eat lunch in the cafeteria at Moorestown (NJ), when I was teaching (high school Spanish) there.

In both cases, above, it comes down to building your staff into a community.

For large hagwon, this could operate on a once-a-week “team lunch” type concept, rotating between different teams of teachers. It can be on-site or off-site (although I prefer on-site, and I think it’s cheaper, too). You will get strong participation if you make the “free meal” part of the perk package, and pay for it out of the hagwon’s operating expenses. This doesn’t need to be expensive food, either.

Idea 5. (Administration / Curriculum.) Month-to-Month Curriculum and Enrollment.

The Korean hagwon market is almost entirely “month-to-month.” Parents are billed month-to-month, and make decisions about enrollment / re-enrollment / cancellation on monthly boundaries. So why do hagwon create complicated multiple-month academic calendars, only to have kids dropping out and in at the most inopportune times (vis-a-vis that same complicated schedule)? There should be monthly progress evaluations. Grades and enrollments should be closed out monthly.

There can be “continuing” curricula, but there should be logical breaking points built on the calendar-month boundaries so that “drop-ins” don’t struggle. Preferentially, however, I’d like to move toward a curriculum system that “closes” each month – that is, no books or materials cross month boundaries. This is because parental investment in curricular materials inevitably makes them reluctant when one wants to accelerate (or more rarely “demote”) students. This is because they want to get their “money’s worth” out materials. Alternately, though, moving toward a strictly in-house production model for curricular materials solves this problem, as materials are then essentially provide gratis.

Idea 6. (Curriculum.) Adopt an Individualized Learning Model

The Negotiated Classroom Environment

Contracts and Empowerment

I still have vivid memories of the novel and unique “contract-based” learning that was used at the Moore Avenue school I attended as a child (grades 1-3). I think that the concept of written contracts with children is exceptional as a means of motivating and making expectations clear, and I’d love to try to develop and apply something like that in a hagwon environment, where it seems even more appropriate (given it’s both a private business and a specialty “after-school” educational institution). It would allow for the hagwon to market itself as highly individualized while not over-taxing teachers with extensive “counselling” duties. Contracts could be based on quantity-of-work metrics (projects completed, workbooks filled out, etc.) and on relative score increases on standardized or specialized level tests (such as the widely used TOSEL tests in Korea, and special interview tests – see below). The whole could be managed with an interactive website.

Clear Expectations (Detailed Syllabus)

Learning as Edifice

Make “project folders” or “portfolios” for students that are kept at hagwon. This is useful with younger ages that have a hard time keeping track of their materials. They should have a “homework kit” and an “at school kit” and the “at school kit” can stay at school, checked out to students as required. This meshes well with Idea 12 (below) on the topic of teachers keeping fixed classrooms.

Do counselling about choosing “best work” for once-a-month selections. There can be derived amazing value from having negotiated class content: setting goals about a) test scores, b) material completion or progress or projects

Idea 7. (HR.) Monthly Teacher and Course Evaluations.

There should be regular objective and subjective teacher and course evaluations, which should not be subsequently ignored by the management. Teachers and courses can also be evaluated on the basis of progress in student scores on standardized and placement tests, which should be administered monthly. Korean parents love objective measures, and hagwon should work hard to generate genuinely meaningful objective measures of both student progress and teacher and course effectiveness (see also curriculum and testing, below). Using free online survey tools is one way to do this cheaply and effectively without eating into classroom time, too.

Idea 8. (Administration.) Simplified Daily/Weekly Schedule, and Consolidated Homeroom and Study Hall for Each Cohort.

Why are hagwon schedules so complicated? I feel as if the typical 200-student hagwon in Korea has a more complex schedule that the average American university. Is this necessary? There seems to be a mindset in Korea that schedules should be complicated, constantly varying and constantly adaptable. This is not entirely alien to US schools either, but the contrast seems to be one of just how important the integrity and constancy of the schedule is. In the US, schedules are changed because of “major events.” In Korea, schedules – even public school schedules – seem to change as a matter of routine. I don’t think it is necessary, nor do I feel it creates an atmosphere conducive to learning.

If I ran a hagwon, I would create a “master schedule” and perhaps one or two “special event schedules” (for parties, informational sessions, special tests, etc.). Then those would be considered inviolable vis-a-vis the other priorities at the hagwon.

There should be a Korean-speaking, consolidated homeroom/”study hall” at the beginning or end of each day’s schedule for each cohort of student. This would be a place to check homework, attendance, pass out memos and other administrative stuff… It would help to keep it separate from classroom face-time for instructors, and provide a chance to check each student’s individual progress in a way that minimizes time wasted in the teaching classroom. Also, it would not necessarily have to employ teachers with a high level of English competency. This would mean that teachers could be hired with other strengths (administrative skills and compassion for students would be notable requirements), probably at a cost savings to the hagwon management.

Idea 9. (Curriculum.) Integrated / Immersive Curriculum, When Possible.

I think it would be more fun for teachers and students to have integrated curriculum (all “four skills” [reading / writing / listening / speaking] combined) with topic-based courses rather than skill-based courses. For example, history class, literature class, debate / discussion class, science class, etc. As well as intensive “clinics” in particular skill areas, prep courses for standardized tests. There could be different, varied and interesting different offerings for each monthly cycle. All offerings could be evaluated for their ability to draw students’ interest and their ability to improve scores on test metrics.

“Kid College” (The “Chinese Menu”)

Idea 10. (Testing.) Testing! Lots of Reliable Testing.

Learn to love the test. I wrote about this quite a while ago, and if anything, over time I’ve become more and more of a believer in this. Rather than follow my US-based, alternative-education background and instincts, which would impel me to reject so much testing, I think instead we should embrace South Koreans’ obsession with testing and leverage it to create a more responsive hagwon system that earns customer loyalty.

Frequent Testing

I have been becoming more and more convinced that the reason English education in Korea focuses so much on teaching grammar and memorizing lists of vocabulary is not, in fact, because they believe that it’s the most effective way but rather that the educators are just simply so desperate for quantifiable results, and they don’t really know how to consistently and reliably quantify other aspects of the language acquisition process. So they stick to those things – prescriptive grammar rules and vocabulary – because that’s what they can easily test and quantify. In light of this, the key to changing method in hagwon instruction is to show that there’s a better way, where you can still get measurable, quantifiable results. That’s why I’m a fan of lots of testing, and not because I believe testing is, in and of itself, a smart thing or the best methodology. But if we are going to improve English education by changing the core subject areas that are taught, we have to prove that there are ways to quantify the other aspects of language knowledge: the pragmatics of speaking, conversation, listening, etc.

Well-Designed Tests and “Teaching to the Test”

Don’t just use standard ABCD multiple choice test formats. There should be something I have been thinking of as a “graded dialogic evaluation” – roleplay-based “situation cards” that students would have to respond to with trained testers, where the situations that needed to be played could be controlled for vocabulary and concept content (e.g. “let’s talk about what you did last year” would be testing things like past tense and vocabulary about activities). They would be graded in difficulty, and in sufficient number that there was a basically random selection (although in free-form [judged] speaking tests, repeated material is not necessarily problematic, since pre -memorization / cheating is nearly impossible). Each month students would take these tests, and scores would be based on “highest level of card” completed along with simple judge-scoring (cf. how TOEFL speaking is scored, 4 point scale). Staff doing the testing would not be the same staff that teaches the students (computers make this kind of administrative task fairly easy). This IS labor-intensive, but I think the value should be immediately apparent. I basically envision dedicated testing days, say two each month, with special schedules.

Make a giant test question database for level testing. Keep track of which questions which students have completed. Keep scores, averages, results, correlates (e.g. offline test scores). For issues surrounding the technical implementation of this idea, see Idea 11 (below).

Idea 11. (Infrastructure.) Leverage free and low-cost technology effectively.

Technology to Support Administration

Technology and the internet doesn’t need to be expensive. Technology can be and should be better leveraged than what I’ve so far seen. Internet Cafes (as Koreans call web forums) can be created for classes. Grades and teacher and course evaluations can be interactive. Writing assignments can be mediated using FREE! tools like Google Apps, rather than crappy ActiveX-based Korea-specific fee-based websites. The web is swarming with fairly effective (and often free or nearly free) software-as-a-service that can keep in-house technology cost and know-how requirements to a minimum.

Technology for Instruction

Technology for Testing

Technology for Marketing

This is, in fact, the only aspect of technology that I view as obligatory as opposed to optional. Technology for instruction, for testing, and even for administration – these are all things that can be leveraged if-and-only-if you can afford to do so. But in Korea’s smartphone-obsessed, internet-driven culture, technology for marketing is a must-have.

Idea 12. (Infrastructure.) Make Your Hagwon A Home.

Overall Environment

“Broken Windows” Policing

Cleanliness and graffiti: there has been a problem with this in every hagwon I have worked at, while at the same time most public schools I have been in have essentially zero problem with this. There are different systems in place. In public schools, students form work details and clean their environment themselves, regularly, with teacher supervision. In hagwon, students are not responsible for cleaning and if they were, parents would complain, since they’re paying “good money” for a privately maintained learning environment. So the hagwon is responsible for their own cleaning maintenance, but there aren’t the same kind of incentives to keep it pristine. I would like to espouse the “broken windows” philosophy, and suggest that learning environments be kept pristine. I’d put the staff to work on periodic cleanup detail, and over time they’d have incentives to better police classroom behavior.

Fixed Classrooms for Teachers

Teachers should have fixed classrooms. In every hagwon I’ve worked at, except the first one under some circumstances, the student cohorts have fixed classrooms and the teachers pass from classroom to classroom. This is perhaps convenient in some ways, administratively, and there’s less confusion and bustle from the problematic of having the students change classes between teaching periods. However, I think it has a lot of disadvantages. One of the foremost is that the teachers don’t have any incentive to personalize their classrooms, and very little impetus or motivation to keep their classrooms clean and well-maintained, etc. The kids write graffiti, things get broken, etc. This doesn’t happen in public schools where teachers “own” their classrooms. Besides, I’d so very much love to have a space I could call my own, to decorate, to personalize. You can put posters, bulletin boards, maps… anything you need or want for teaching.

A question to meditate on: who is the staff room for? How does this fit into the priorities of a hagwon?

Invest in Classroom Comfort

It would be nice, too, if there was sound proofing / spacing and volume in classrooms

Arrangeable desks are best: arcs, circles, facing rows, groups… (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harkness_table)

Idea 13. (HR.) Non-stop Teacher Training.

Pedagogical and Methodological Training

Businesses should not be afraid to dedicate resources and time to staff improvement. Teachers working at Korean hagwon often have many years of teaching experience, but they rarely if ever have any formal background in pedagogy or teaching methodology. I think this can make for significant mistakes in curriculum design and development, not to mention implementation and classroom management issues. There should be opportunities within the work environment allowing teachers to learn about child psychology, pedagogy, and education theory, methodology and practice.

Language Training specifically is covered under Ideas 1 and 2, above.

Idea 14. (Curriculum.) Curriculum Design.

Put Testing at the Center

Pedagogically, this is controversial, but in the Korean cultural and educational context, inevitable. So rather than fight it, embrace it. The key, if you’re going to be teaching to the tests, is to have impeccably designed and administered tests.

Parallel Tracks (Athens vs Sparta)

A hagwon could be very successful if it had “Parallel tracks” which you might term “traditional/academic” versus “creative/immersive.” I’ve been thinking, especially, about what might be characterized as the “fun vs work” dichotomy in parental expectations.

Some parents send their kids to hagwon with the primary intention that it be mostly “fun” or that it be educational but not, per se, stressful or hard work. I’m speaking, here, mostly about elementary-age students. At middle school and high school levels, the situation is substantially different, at least here in Korea. It’s mostly about raising test scores, at those levels. But at elementary levels, it’s definitely the case that many parents aren’t looking for an academically rigorous experience so much as a kind of enriched after-school day care.

But then there are the parents already looking for the hagwon to inculcate discipline and hard work habits and raise test scores, even at the lower grades. They get angry and feel they’re not getting their money’s worth when their kids don’t have a lot of homework, for example.

This creates a dilemma in managing the hagwon, because you have kids from both groups side-by-side in your classroom, and you have to be aware of that. I have exactly this, every day: Kid A and Kid B didn’t do their homework. Sometimes, when kids haven’t done their homework, we have a custom of making the kids “stay late” (after the end of their particular schedule of classes) to finish their homework or do some kind of extra work to make up for the missed homework. And the problem becomes manifest when Kid A’s mom complains that we’re not making her stay often enough, while Kid B’s mom complains that we’re making her stay at all. You can see the conflict, right? It creates inequalities in how we treat different students in the classroom, that eventually the students themselves become aware of. And that leads to complaints of unfairness and classroom management issues, too. Eventually, there comes a moment when Kid A is asking me why I’m not making Kid B stay. I can’t really come out and say, “well, her mom complains when I make her stay, but your mom complains when I don’t make you stay.”

Here’s how I think it should be solved.

The hagwon should have two parallel “tracks” – a “fun” English and an “un-fun” English. Tentatively, because it’s marketing gold, I would call these “Athens” track and “Sparta” track.

The Sparta track would be about what we have now: lots of grammar, daily vocabulary tests, long, boring listening dictation work, etc. The Athens track would be my “dream curriculum” with arts, crafts, cultural content, karaoke, etc. There would be some shared or “crossover” classes, like maybe a debate program for the advanced kids or a speech program for the lower-ability ones, to ensure everyone gets some speaking practice.

The advantage of these two parallel tracks is that kids could be placed into either track based on parental preference. Further, parents could move their kids back and forth between them, depending on changing goals or needs. And lastly, the kids themselves would be aware of the dichotomy, and there could be substantial incentives related to the possibility of being able to be “promoted” to the fun track or “demoted” to the un-fun track. It would require careful design, but I think it could be a strong selling point when parents come in to learn about the hagwon. That we have not one system, but two, enabling a more individualized style of English instruction.

On-Going Roleplay Environments.

Have large on-going roleplay environments: “town” / “stock market” / “country”

I did this very successfully during my summer camps at my public school teaching job in 2010. Very rarely, since, have I had students more actively engaged in their own learning process. They were learning English painlessly, because it was interesting and fun.

Idea 15. (Administration.) Customer Relationship Management (CRM).

In business contexts (at least in the US, where I have experience) there is a broad field or discipline – generally embedded in the sales and marketing departments of large corporations – called “Customer Relationship Management” or CRM for short. This is about channeling, controlling and focusing all interactions with customers to maximize customer satisfaction.

To be clear, when I refer here to CRM I am not referring to a technology but to a practice – CRM is a “way of doing business” which is often enabled by technology in large businesses, but is just as doable using index cards or a large spreadsheet in a small business, even doable entirely in the mind of the business-owner in an owner-operated business such as a “mom and pop” hagwon, as was the phenomenal case of the first hagwon I worked at, where the owners knew by name every single parent, and interacted them with on a weekly basis.

As a specific example, I was sharing with my boss an opinion: given that a lot of parents are expressing distrust of the merger between Karma and Woongjin, he should call them all, personally. That’s always been one my “if I ran the hagwon” ideas, anyway – the owner or on-site manage should be intimately involved in building and maintaining relationships with ALL the parents, since they are, after all, the paying customers. The students, for better or worse, are essentially just products. This is not to depreciate them in any way – they are the thing I like about my job, and they are why I do it. But applying the lessons I learned from a decade of working in real-world business settings, you can’t ever forget your customers. My boss has been stressed, lately, though. In response to my suggestion, he just said in a kind of a lighthearted way, “개소리” [gae-so-ri = “bullshit” (literally, it means “dog-noise”)]. It was kind meant as, “yeah, right, like I’m going to find time to do that.” I laughed it off. And my feelings were in no way hurt. But I nevertheless felt (and feel) that he’s making a mistake in this matter, maybe.

Some Customers Aren’t Worth It.

“Fire” the parents that don’t “fit.” Hagwon parents are so hard to please, of course. One parent complains of not enough homework, and another complains of too much. How can one respond? Often what happens is that you give lots of homework, and there will be a kind behind-the-scenes understanding that not all the kids are being held to the same standard, as driven by parental expectations or requirements. The conversation essentially goes like this: “Oh, that kid … his mom doesn’t want him doing so much homework, so don’t worry if he doesn’t pass the quiz, just let it go.” This grates against my egalitarian impulses, on one level, and on another, despite being sympathetic to it, I end up deeply annoyed with how it gets implemented on the day-to-day basis: due to poor communication among staff, no one ever tells me these things until some parent gets mad because I never got told, previously, about the special case that their kid represents. In the longest run, of course, in the hagwon biz, one must never forget who the paying customers are – it’s the parents. And for each parent that is pleased that their kid is coming home and saying “hagwon was fun today,” there’s another that takes that exact same report from her or his kid as a strong indicator that someone at the hagwon isn’t doing his or her job. So it boils down to this: happy hagwon students don’t necessarily mean happy hagwon customers. As a teacher, you’re always walking a tightrope: which kids are supposed to be happy, and which are supposed to be miserable? Don’t lose track – it’s critical to the success of the business.

Example of a problem: a student is caught cheating. So the student is challenged by the teacher and corrected, but then the student complains to his or her parents that the hagwon is too stressful and wants to quit, and the parent pulls the student. That’s lost revenue. That really happens. Does that mean a hagwon shouldn’t correct students caught cheating? Or does it mean that there is a certain quality or type of student (and / or parent) that is learning at a level that the hagwon shouldn’t pursue as a customer?

Idea 16. (Administration / Finance / HR.) Experiment with Empowering All Stakeholders (Owners, Staff, Customers, Students.

One thing that I have always wondered about as a possible solution to the way that capitalism distorts the hagwon business in Korea is to introduce a kind of cooperative or mutualist or profit sharing model, like some companies in the U.S. What if customers received some profit-sharing refund at the end of year, pro-rated against what they had paid? I can imagine that would lead to improved loyalty as well, especially if there were vesting. That kind of thing could be even more motivating for staff.

Idea 17. (Administration / Curriculum.) Predictable Costs for Customers (i.e. flat rate supporting materials charges).

The main idea here is that the hagwon pays for whatever specific materials (books, notebooks, CDs / mp3 files, etc., that are needed for the curriculum. If they want to encapsulate that in a fixed-fee materials-support charge of some kind, that might be possible, but overall I think the market might welcome a more reliable flat-rate system where per-hour-of-instruction charges were slightly higher but additional materials were all “included.”

I have heard that it is no longer “legal” for hagwon to charge for books or supplementary materials, but I also know from personal work experience at multiple hagwon that it is still almost universal practice, at least in my area. I think this is one area where government regulation is pushing hagwon in a direction I consider appropriate.

Idea 18. (Administration / Curriculum.) No “Staying Late” Beyond Study Hall or Homeroom (see Idea 8 above).

It’s common in hagwon to make kids stay late, either as punishment or as catch-up on undone homework or failed quizzes. I think this a poor practice for one key reason – it ends up not being fair. Some kids’ parents don’t want them to stay late. Some kids have other obligations. Sometimes, if the students are in the last “shift” of the day, they can’t stay late because schedule of regular classes runs right up against the deadline when hagwon must close by law. It’s better to never make kids stay late.

I have heard that it is “illegal” to do this, now, under current government regulations, but I know too that many hagwon still engage in this practice quite extensively, and it ends up being a burdon not just for students but also for parents and especially teachers, since this out-of-classroom “detention” time ends up being essentially uncompensated teaching.

The end to “stay late” practices could be presented to parents along with an explicit commitment to parents to instead provide additional tutorial or academic support on a per half-hour charge basis of some kind. This could provide an additional income stream to the hagwon but will be met with some resistance by parents, many of whom still seem to insist that the extra tutorial effort be “included” in the tuition price. This resistance could be overcome through measures such as greater transparency or profit-sharing (see Idea 16) as well as the fact that other costs are better controlled (e.g. textbook and class materials, see Idea 17, preceding).