[In the form of various unstructured entries with fairly random thoughts, I’ve been working on this project for several years, and it’s come to have the name “If I Ran The Hagwon” (abbreviated as IIRTHW). This topic seems to be evolving into my first effort at something resembling long-form journalism on my blog. Here is Part II. I posted Part I last month. Additional parts (number to be determined) will follow.]

[Part I]

Part II – The Business Environment.

To understand what would make a better English language hagwon, it’s important to get some broad understanding of the business and cultural context in which a typical hagwon has to operate these days.

There are many aspects that make the hagwon environment “alien” to people from Western countries (and even, to some extent, perhaps other non-Western countries too). I’d like to talk about these aspects. In fact, they all derive from a single overarching fact: the hagwon “system” as it currently exists in South Korea is an example of unbridled capitalism in the field of education. This basic fact leads to a whole bunch of concomitant issues that come to our attention once we understand it.

Since I believe that ultimately, the key to success in business is customer loyalty, regardless of the business in question, I will try to connect each of these observations to the concept of customer loyalty. This will provide a sort of unifying theme for this exercise.

1. Alienation and workplace regimentation.

A core fact of capitalism is that it leads to alienation. South Korea’s capitalist economy doesn’t just generate alienation, but requires alienated, conforming workers as a precondition to function efficiently. This being the case, one of the purposes of South Korean education is to create appropriately alienated workers out of whole human cloth. Because of this, just like the military (another alienation-making-machine), Korean schools and hagwon have as a key non-explicit mission the alienation of students.

It’s hard to explain how important this is to the ultimate character of the hagwon business environment. Setting aside complex questions of what teaching methodologies actually work and what ones actually don’t work in a wider, theoretical context, in South Korea, specifically, there isn’t a lot of cultural space for what we might think of as empowering styles of teaching.

Korean students tend to be fairly passive, and require a fairly high level of supervision and extrinsic motivation. Efforts at cultivating intrinsic motivation will create discomfort and even suspicion among not just students but, more importantly, among parents and fellow teachers, who will ask questions such as, “why are you letting this child have fun at school? How is that going to help little Haneul for her next test?”

I might state, just as an observation for future reference: suspicious customers are not loyal customers.

2. Parents-as-consumers, children-as-products.

One thing that even the Korean hagwon owners rarely seem willing to admit is that on this capitalistic model, the children are not our customers. They are not paying the bills. The children are essentially products. I don’t mean this in a necessarily bad way – it’s just the reality and it’s better to have a firm grip on the reality. To be more precise, the students’ hopefully improved test scores are a service being provided. In light of this, a bad test score is emblematic of a defective service, and will lead very quickly to lost customer loyalty.

Nevertheless, within this conceptual frame there is still a lot of room for variation. Different parents have different opinions as to how they want their kids’ scores improved, and they may have various rigid or not-so-rigid views as to what methods should be used. They may be sophisticated consumers of education or naive; they may be traditionalists or innovationists.

Identifying and catering to these different types of parents (i.e. customers) is the key to acquiring and retaining their loyalty.

3. Market fragmentation and niches.

Given that some 80% or 90% of Korean students attend some form of hagwon, the market is huge. Although Korea is not an ethnically diverse country, it is an ideologically and culturally diverse one, with parents running the gamut from communards to vaguely Randian libertarians, from atheistic hippies to Pentecostals to Buddhists.

Education is (has been, will always be) an area where ideologies and subcultures play a major role, and capitalism is a system that encourages market fragmentation. The consequence of this is that there is a nearly infinite number of possible market niches out there. Not all of these market niches are viable, but I think this insight underscores one very important point: a given hagwon – especially a non-chain, “mom and pop” style, single-location hagwon – can occupy one or more of any number of possible market niches, providing anything from “fun English” to “hardcore pass-the-test cram English.”

4. The importance of “counseling” (상담).

The Korean word is 상담 [sangdam]. It means, roughly, “counseling.” In a customer-oriented business (e.g. telecoms) the work the people who talk to you on the phone trying to sell you stuff or solve your problems is called 상담. In the context of running a hagwon business, too, I would argue that is, in essence, a sales position. Rather, it is not just sales, but the after-the-sale “account manager” position common in large, service-oriented businesses.

Hagwon counseling includes mostly telephone “counseling” but also plenty of face-time with parents, too. If counseling is so critical, why do so many hagwon force the teachers into this critical, customer-facing position? Let’s take note of something: good teachers are not necessarily the best sales people. And good sales people are not necessarily the best teachers.

Obviously, in many people, there is some overlap – the skill sets are not, in fact, dissimilar. Conceding that fact, however, if I was running a small business I would work very hard to make sure that anyone who dealt with parents in this counseling role had lots of innate talent and lots of training (training in that account manager style counseling as opposed to just training as teachers) and that those counseling-based, customer-retention statistics (as compared to statistics linked to things like quality-of-teaching or student test

score outcomes) were tracked and documented.

In a small hagwon, this counseling role can be consolidated into a single person’s role. It can be that person’s sole job in a slightly larger institution, and in a large, successful hagwon, I can imagine a whole cubicle farm of “customer account managers” whose sole job is keeping parents satisfied.

This leads to a certain complication, however: if the sales people (the account managers) aren’t the same ones teaching the kids, there needs to be very clear lines of communication – a centralized database of student progress, teacher observations, parent requests, etc. I’ve never seen anything resembling this in the hagwon business.

This is where providing some reliable means of communication between teachers (service people) and counselors (sales people) is critical.

Just remember what this really boils down to: marketing is king.

5. The purpose and deployment of technology.

Technology is popular in Korean classrooms – more so in public schools than in hagwon, but certainly in hagwon too. I think it’s critical to understand one core fact – for a hagwon, where costs are critical and methodologies trend toward the traditional, technology is 95% marketing, and at best only 5% pedagogy. In other businesses I’ve been a part of in the U.S., in the past, technology is what is sometimes called “the bells and whistles.”

Perhaps it doesn’t help that I, personally, have always been severely skeptical of the genuine usefulness of technology in pedagogy. I think you can create a world-class school with chalkboards and dirt floors, and you can create content-free educational pap with computers, video conferencing, etc. There are definitely some things of great value. I love using a video camera to put the pressure on my students, to evaluate them, and later to review our progress. But I view it as unnecessary and irrelevant from a pedagogical standpoint. It’s “bells and whistles.”

Customers, on the other hand – the parents – have great interest in these bells and whistles. It’s smart to try to leverage our technology in ways that make customers feel like they’re getting something extra, something personalized, something valuable. Building and leveraging social web tools is critical, probably. My only point here is that we must never lose sight of the core fact: it’s about marketing.

Marketing is king.

6. Do all customers have the same value?

As mentioned above, the market is fragmented. That being the case, it’s critical for hagwon to identify and occupy specific market niches. Most of them do, but they often do so rather naively – which is to say, they occupy the niche without a clear understanding that that’s what they’re doing.

To get a leg up on the competition, explicitly identifying and pursuing specific market niches is indispensable. There should be a lot time spent figuring out what niche to pursue, and in recognizing that not all customers are the same. Different parents have different expectations, and different children have different needs. We

shouldn’t try to be all things to all people.

This idea leads to a corollary: sometimes it’s OK to tell a customer we don’t want them. Some customers are not “worth the trouble.” I like to think of Steve Jobs, who famously didn’t give a damn about customers who didn’t like his product. He would typically say something to the effect of: “Let them buy someone else’s product, if they don’t like mine.”

Likewise, the pursuit of customers just for customers’ sake is a really bad idea. I have seen hagwon management investing far too much energy and time and teacher goodwill in trying to satisfy parents or teach children where it’s clearly not in the hagwon’s interest to do this. Let bad customers go. Identify the good customers and work hard for them and earn their loyalty, but acknowledge that not all customers are the same, and some customers can’t be pleased.

We should be efficient. We should measure just how much effort a customer is requiring of us, and have a “cut line” whereupon we have to say, “I’m sorry, but I think this relationship isn’t working out.” Big companies do this very well – that super friendly and helpful customer service rep you spend so much time with is being kept track of, and there will be a point when his or her boss will tell him, “let that customer go.”

7. Reliable curriculum vs innovative curriculum.

The purpose of having a reliable curriculum is pedagogical. By reliable, I mean that it produces consistent and predictable results, which, in the hagwon context, of course, means rising test scores and satisfied parents. The fields of EFL pedagogy and teaching methodology may or may not have a great deal to offer on this front, but what I want to address here is something else.

A lot of hagwon try to convince themselves or their customers that they are providing innovative curriculum. This does not serve a pedagogical purpose – it’s a sales gimmick. In this way, innovation in the area of curriculum mostly serves a purpose similar to that identified with respect to technology, above: curricular innovation is a component of marketing and niche-building.

Innovation is perhaps required if a current curriculum isn’t producing hoped-for results, but in the long run, if a curriculum is producing results, innovation is a bad thing, not a good thing. Innovation makes loyal customers uncomfortable and more often than not fails to impress new customers. It’s better for a business to find what’s working and stick with it, and most successful hagwon seem to operate this way.

8. The demographic problem.

South Korea has a demographic time-bomb ticking. The fertility rate has dropped far below replacement rate, immigration is still low relative to most OECD countries, and furthermore structural and social problems mean that despite this, youth unemployment is quite high.

That’s not what I want specifically to talk about here. What’s critical for someone wanting to run a hagwon business in Korea right now is the understanding that, beyond what I just mentioned, education is a shrinking market – and there’s absolutely nothing that can be done about it.

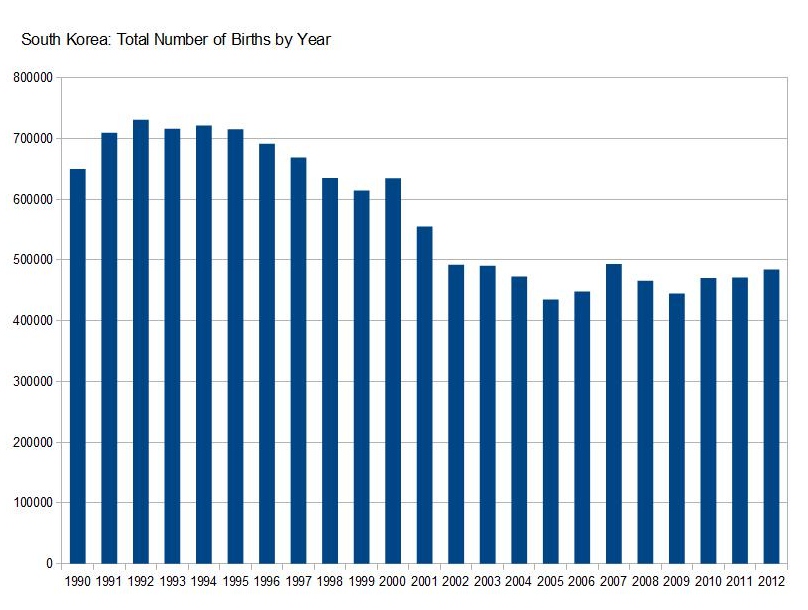

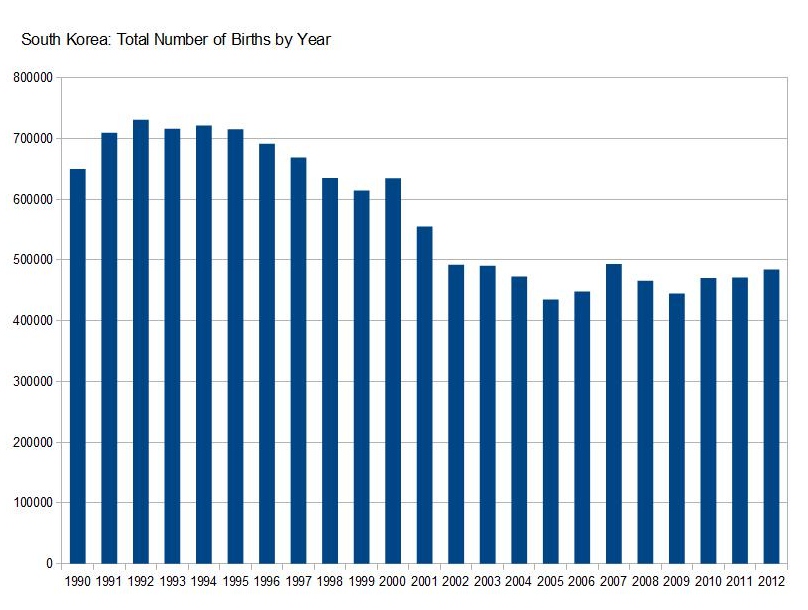

I made the graph below using data from Wikipedia (sourced, in turn, from a Korean government agency).

This graph makes very clear two things. First of all, explains why the elementary hagwon business was booming when I first arrived in Korea, in 2007. The 1990’s bulge on the left of the graph was just passing through the elementary system. Secondly, though, it explains why that boom was utterly unsustainable, moving forward, and why hagwon are struggling to find new elementary students to teach. Quite simply put, there are fewer students entering the system. The number of births suffered a precipitous decline of more than 20% in a single decade, and has stabilized at a new, much lower level. The number of hagwon in business in the 2000’s is unsustainable in the 2010’s.

This being the case, it underscores the importance of two things I’ve already mentioned. Customer loyalty is crucial. But also, in identifying a niche in which to operate, the focus should be on quality rather than quantity. The so-called upmarket niche is the only one sustainable or growable given current demographics. We can’t be churning out PC clones, we have to be making the Macs or Sparc workstations of the hagwon business.

Conclusions.

The preceding has been my effort to make a list of some of the issues that face the hagwon business in South Korea, as I have experienced them. It’s not meant to be an exhaustive list, and it may in fact have substantial lacunae. It’s only things as I have seen them, with an emphasis on the things that seemed most notable to me.

But I think they provide some idea as to the business and cultural context in which a successful hagwon must operate.

In my next part, I want to go on to the original purpose of this essay: what makes a good hagwon? How can I make one? What would I do if I could make one as I wanted?

[Part III]